Mechanochemical-Aging Synthesis of Bismuth Oxide Nanosheets for Photocatalysis

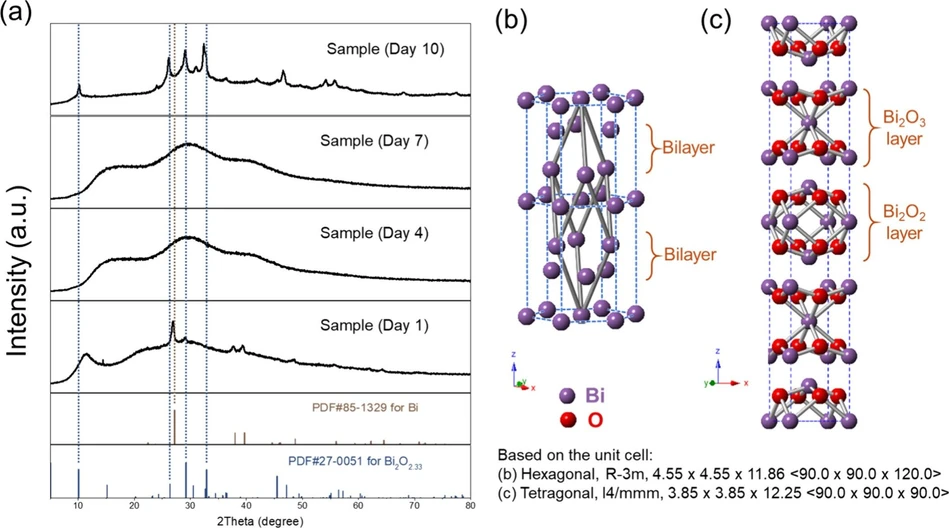

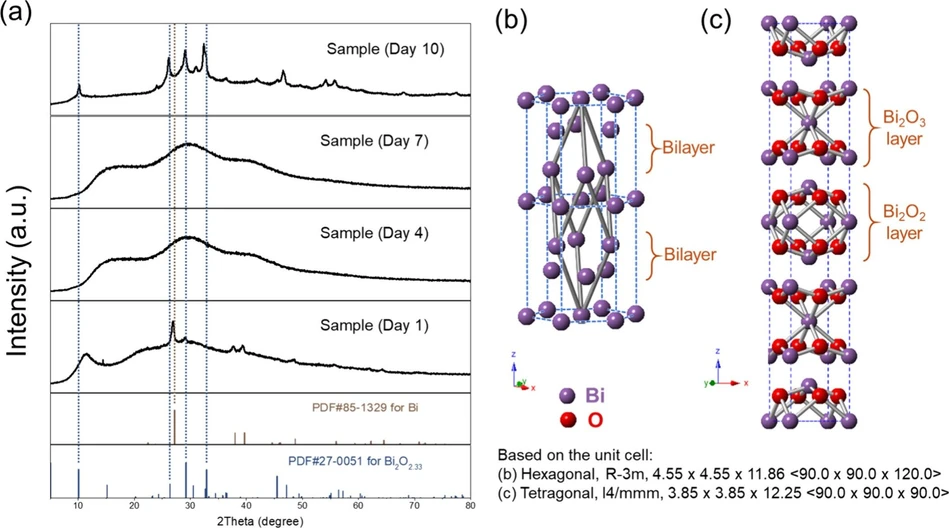

ACS Mater. Au 2025: Figure 2. Structural evolution for the mechanochemical-aging synthesis process. (a) XRD spectra of samples collected on Day 1 (freshly made) and Days 4, 7, and 10 with the standard PDF reference cards for metallic Bi and nonstoichiometric Bi2O2.33. Schematic presentation of the crystal structures of (b) metallic Bi and (c) nonstoichiometric Bi2O2.33

Mechanochemistry offers a green, solid-state pathway for designing nanomaterials, while chemical aging provides precise control under mild conditions. This study combines both methods to create nonstoichiometric bismuth oxide nanosheets with exceptional adsorption and photocatalytic performance toward persistent organic pollutants.

Detailed structural and compositional analyses revealed that strain-induced defect formation during grinding followed by chemical delamination under aging leads to the formation of defect-rich Bi₂O₂.₃₃ nanosheets. This mechanochemical-aging synthesis provides new insight into two-dimensional metal oxide design and expands the potential for sustainable nanomaterial production.

The original article

Mechanochemical-Aging Synthesis of Bismuth Oxide Nanosheets for Photocatalysis

Delaney J. Hennes, Luke T. Coward, Chase G. Thurman, Oksana Love*, and Pin Lyu*

ACS Mater. Au 2025, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX

https://doi.org/10.1021/acsmaterialsau.5c00104

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Mechanochemistry, old techniques with new perspectives, has been reawakening the passion for exploring solid-state approaches toward chemical transformations and materials synthesis in a green and sustainable manner, due to its intrinsic solvent-free and eco-friendly nature. (1−8) More importantly, the driving force of the mechanochemical process, mechanical force, has provided a fundamentally different reaction pathway by promoting intensive, well-oriented, and effective molecular collisions and creating molecular strains and structural defects, (6,9−13) compared to the conventional thermal or electrostatic driving forces. This perspective has opened new avenues for well-defined nanomaterial synthesis with unique structure–property relationships that the conventional solution-based methods cannot achieve, as well as in a greener way. (4,14−17) Recent reports have demonstrated great potential in designing metal and metal oxide nanoparticles, (17,18) nanocomposites, (19) and hybrid porous materials such as metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) with desired properties. (20−22)

In terms of 2D nanostructure design, two traditional approaches─bottom-up and top-down synthesis─have been widely developed in various synthesis strategies, offering precise control over size, shape, morphology, and dimensions. (23,24) The formation mechanism behind the scenes can be monitored and reasonably interpreted by advanced in situ spectroscopic (25−27) or microscopy methods, (28−30) to identify the critical factors in the structure transformation that lead to property-on-demand synthesis. Specifically, in 2D metal oxide nanosheet synthesis (Scheme 1), chemical vapor deposition, solvothermal method, and chemical exfoliation represent three typical methods. The first two methods start with molecular or atomic precursors for self-assembly growth, while the last method utilizes bulk layered host materials for layer-by-layer delamination. However, these methods rely on sophisticated instrumentation, harsh synthesis conditions, excess solvents, or toxic exfoliating chemicals, which limit their potential scalability.

ACS Mater. Au 2025: Scheme 1. Comparison of Conventional and Mechanochemical-Aging Methods for Bismuth Oxide Nanosheet Synthesis

ACS Mater. Au 2025: Scheme 1. Comparison of Conventional and Mechanochemical-Aging Methods for Bismuth Oxide Nanosheet Synthesis

Mechanochemical synthesis, with its all-solid-state, solvent-free nature, provides an alternative approach. This approach introduces an external applied physical force to initiate intense molecular interactions for mixing and growing (bottom-up) or to spread the shear stress or shock impact uniformly for deformation or delamination (top-down). It has been elegantly demonstrated in various traditional two-dimensional materials syntheses, such as graphene, (31) MXenes, (32) and transition-metal dichalcogenides. (33) Specifically, for bismuth-based materials, nanosheets of bismuthene, (34) bismuth oxyhalides, (35) and bismuth nitrates (36) have been reported previously with the mechanochemical methods. Meanwhile, very few reports are focused on metal oxide 2D nanostructures, probably due to the relatively higher interlayer interactions in those host materials. Thus, a follow-up process is needed to accelerate delamination of the mechanochemically produced bulk materials into the desired 2D nanosheet structure. Recently, Moores’s and Friščić’s groups have successfully demonstrated the combination of mechanochemistry and aging for the extraction and functionalization of biomass derivatives, (37,38) and functionalized inorganic metal or binary nanoparticle synthesis. (39,40) Aging, as a spontaneous diffusion-controlled process, can be controlled by the chemical reactivity and solution environment to induce material transformation, further advancing to the targeted structures while minimizing reagent and energy use. (40)

In this work, we developed a mechanochemical-aging process to synthesize nonstoichiometric bismuth oxide (Bi2O2.33) nanosheets, which demonstrated excellent performance in the adsorption and photodegradation of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA). Through the observation of morphological, crystal structure, and surface chemistry changes during the aging process, we propose a strain-to-defect growing mechanism. Mechanical force exerted on metal precursors and reducing agents during solid-state grinding can induce rapid and intense molecular collisions, leading to the generation of strain-rich metallic nanostructures. The following aging process, occurring in an aqueous surfactant-deficient environment, can delaminate the bulk structure into well-defined 2D nanosheets over time with the assistance of ambient oxygen. This approach could potentially be applied to other 2D metal oxide nanostructures.

Experimental Methods

Chemicals and Characterizations

All chemicals and reagents were used without any purification. Bismuth(III) nitrate pentahydrate (99.999%, trace metal basis), PVP (M.W. 40,000), and sodium borohydride (99%, powder) were purchased from Thermo Scientific Chemicals. The morphology and elemental mapping analysis of bismuth oxide nanosheets (Bi2O2.33 nanosheets) was examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-IT700HR, 15 kV, JEOL) with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, 0–20 kV energy window, Ultim Max 40: UVA13205 detector, Oxford Instruments). The evolution of the local crystalline structure of Bi2O2.33 nanosheets was monitored by a powder X-ray diffraction pattern (PXRD, Bruker D2 PHASER Benchtop XRD, Cu tubes, 30 kV, 10 mA) and was processed with DIFFRAC.EVA data analysis software with the Crystallography Open Database (rev.278581). The surface status of functional groups was determined by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Shimadzu IRSpirit, 16 scans collected with a resolution of 4 cm–1) with the attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode. The quantification of the PFOA (C7F15–COOH) and its degradation intermediates, perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA, C6F13–COOH) and perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA, C5F11–COOH), was determined by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS, LCMS-8040 Triple Quad LC-MS/MS, Shimadzu Scientific Instruments) in negative electrospray ionization mode. Separation of analytes occurred with the use of a binary solvent gradient between 5 mM ammonium acetate in H2O and methanol that ramped from 5% methanol at 0–3 min to 40% methanol from 3 to 16 min and 80% methanol after 16 min. Each liquid was passed through a Phenomenex C18 column (1.8 μm, 100 × 2.1 mm) at a constant oven temperature of 40 °C with a solvent flow rate of 0.25 mL per min. The elution of PFOA occurred at 15.7 min, PFHpA at 13.2 min, and PFHxA at 11.6 min. A 13C isotope-labeled PFOA internal standard (Wellington Laboratories) was paired with a 12C native PFOA solution to quantify each sample’s concentration. The standard curve for PFOA quantification ranges from 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 ppb, with a limit of detection of 3.6 ppb and a limit of quantification of 11.1 ppb.

Results and Discussion

To pinpoint the growing mechanism behind the mechanochemical-aging process, morphological, crystal structure, and surface chemistry changes are monitored by using SEM, XRD, and FTIR, respectively. First, after freshly grinding, the gray powder was sent for XRD testing, as shown in Figure 2a as Sample (Day 1). All of the observed diffraction peaks match well with the standard PDF card of metallic bismuth, indicating the successful reduction of molecular bismuth precursors. There is a small peak around 12 degrees, which matches one of the broad peaks of PVP powder (Figure S1), which is anticipated at this stage since the PVP used in the precursor mixture is 5 times the weight of the bismuth salts and has not been washed away. There is another small peak around 29° that matches nonstoichiometric bismuth oxide, which will be discussed below. According to the previous report, (50) the overall hexagonal crystal structure with a rhombohedral unit cell (as shown by the gray connections in Figure 2b) is commonly observed at ambient conditions for metallic bismuth. Two bilayers within the hexagonal structure are separated by relatively weak van der Waals-like interactions, which provide space and relatively low energy barriers for the following aging process. As follows, during the aging process, with the assistance of PVP surfactant solutions and dissolved ambient oxygen, the metallic Bi gradually oxidizes, and the crystal structure becomes more amorphous, as observed with 3 broad peaks of XRD patterns in Day 4’s and Day 7’s samples. The PVP peaks are not observed in these samples in the XRD, possibly due to the disruptions of the ordered structure in the powder form when they are dispersed in a low concentration solution (0.5 mM). Eventually, on Day 10, a fully oxidized sample is formed, with a crystal structure matching the nonstoichiometric Bi2O2.33 standard card, and no distinct peaks are observed for metallic Bi anymore. Additionally, Figure S2 compares standard patterns for bismuth subcarbonate and three distinct phases of stoichiometric bismuth oxide with those of the Day 10 sample. None of these reference patterns match the observed pattern of the Day 10 sample, ruling out the presence of these phase impurities in our material. This mixed-valent (Bi2+ and Bi3+) electron-rich structure of nonstoichiometric Bi2O2.33 was previously reported in research using traditional synthesis methods mentioned above, which demonstrated excellent properties, such as UV-emitting photoluminescence, supercapacitance, ferromagnetism, and photocatalysis. (41,43,47) To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports on the mechanochemistry-driven synthesis of this unique structure. To be specific, as shown in Figure 2c, the overall tetragonal structure consists of a mixture of Bi2O3 and Bi2O2 layers within the lattice, possibly coming from the oxidation of metallic bismuth in the original bilayer structures before aging. This unique structure, featuring the stereochemically active lone pair of Bi3+ and the electrostatically electron-rich site of Bi2+, could potentially contribute to interlayer flexibility and defect formation, ultimately leading to the final nanosheet structure. This has been observed in other bismuth-based materials with preferred layered structures as well. (51−53)

ACS Mater. Au 2025: Figure 2. Structural evolution for the mechanochemical-aging synthesis process. (a) XRD spectra of samples collected on Day 1 (freshly made) and Days 4, 7, and 10 with the standard PDF reference cards for metallic Bi and nonstoichiometric Bi2O2.33. Schematic presentation of the crystal structures of (b) metallic Bi and (c) nonstoichiometric Bi2O2.33.

ACS Mater. Au 2025: Figure 2. Structural evolution for the mechanochemical-aging synthesis process. (a) XRD spectra of samples collected on Day 1 (freshly made) and Days 4, 7, and 10 with the standard PDF reference cards for metallic Bi and nonstoichiometric Bi2O2.33. Schematic presentation of the crystal structures of (b) metallic Bi and (c) nonstoichiometric Bi2O2.33.

Moving forward, the SEM images of freshly made (Day 1) samples and samples at different intervals during the aging process were collected for tracking morphological changes, along with EDS mapping to confirm the elemental composition and compare the spatial distribution of these elements. As shown in Figure 3, the bulk rod microstructure of metallic Bi after grinding and washing on Day 1 was observed with a relatively small amount of well-defined hexagonal thin nanosheets. These nanosheets have a relatively smooth surface, and the edge length is about 1 μm with a lateral width of 2 μm. The EDS full-range scan results also confirmed the dominant element compositions of carbon, oxygen, and bismuth in Figure S3, in which the carbon comes from both the carbon tape used in the sample preparation and the PVP polymer residues. For the EDS mapping in Figure S4, the distributions of Bi and O are relatively and consistently uniform across the sample, while the oxygen amount is significantly higher than the bismuth (estimated based on the spectra intensity counts and relative atomic mass). It is possible due to the residual PVP polymer still adsorbed on the surface, and is ready to participate in the next delamination process. This is also observed in the FTIR spectrum of O–H bending, C–H bending, and C–N stretching, possibly from the PVP, as shown in Figure S5, compared to the FTIR spectrum of PVP powder. It is noteworthy that very weak Bi–O bonding and a hydrophobic surface with almost no O–H stretching are also observed in Day 1’s sample, combined with the evidence of PVP, dominant metallic Bi peaks, and a small peak of Bi2O2.33 from the XRD analysis above. It is suggested that after freshly grinding, the metallic Bi bulk microrods formed as the aging precursor for the subsequent delamination process, and small amounts of oxide nanosheet structure began to form adjacent to the bulk rod, indicating a delamination pathway rather than nucleation from the aging solution.

ACS Mater. Au 2025: Figure 3. Morphology evolution for the mechanochemical-aging synthesis process. SEM images of samples collected on (a–d) Day 1 (freshly made), (e–h) Day 4, (i–l) Day 7, and (m–p) Day 10.

ACS Mater. Au 2025: Figure 3. Morphology evolution for the mechanochemical-aging synthesis process. SEM images of samples collected on (a–d) Day 1 (freshly made), (e–h) Day 4, (i–l) Day 7, and (m–p) Day 10.

Conclusions

In summary, we developed a mechanochemical-aging approach for the synthesis of nonstoichiometric Bi2O2.33 nanosheets, exhibiting excellent adsorption capacity and photocatalytic degradation performance toward forever chemicals. Different stages of morphological, crystal structure, and surface composition changes were observed and correlated to our proposed growth mechanism. Our mechanistic interpretation focuses on the effects of transient strain accumulation and relaxation resulting from applied mechanical forces during grinding, as well as controllable chemical delamination through capping ligands and oxygen amount during aging. This mechanism features strain-to-defect transformations at the molecular-to-crystal level, which could potentially extend to other 2D metal oxide nanostructure designs.