Dissecting Heterogeneous Populations of Protein-Complex Samples Using Direct Mass Technology

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 49, 27057–27063: Graphical abstract

Charge detection mass spectrometry (CDMS) allows direct mass determination of individual ions and is increasingly used to study heterogeneous biological samples. This work demonstrates the use of Orbitrap-based CDMS/Direct Mass Technology (DMT) for quantitative analysis of transthyretin (TTR) tetramer samples below 100 kDa, extending CDMS beyond its traditional qualitative role.

DMT resolved wild-type and C-terminally modified TTR homotetramers, as well as hybrid tetramers, enabling kinetic analysis of subunit exchange and stability. The approach also quantified thyroxine binding to TTR variants, revealing differences in binding affinity linked to C-terminal modification. By separating overlapping m/z signals through charge measurement, CDMS enables accurate mass and abundance determination, highlighting its potential for quantitative analysis of complex protein systems.

The original article

Dissecting Heterogeneous Populations of Protein-Complex Samples Using Direct Mass Technology

Robert L. Rider, Jared Hampton, Zhenyu Xi, Carter Lantz, Sangho D. Yun, Weijing Liu, Rosa Viner, Arthur Laganowsky, and David H. Russell*

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 49, 27057–27063

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.5c05771

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Transthyretin (TTR) is a homotetrameric transport protein that circulates in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid, delivering thyroxine (T4) and retinol-binding protein–vitamin A complexes. (1) The stability of the TTR tetramer is central to its physiological role because dissociation into monomers can initiate misfolding and amyloid formation, leading to systemic or hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. (2) Subunit exchange between wild-type (WT) and variant TTR proteoforms, including disease-associated mutations such as V30M and V122I, have been implicated in amyloid progression by generating hybrid tetramers (tetramers containing WT and mutant subunits) with altered stabilities. (3,4) Ligand binding, particularly at the two thyroxine-binding sites located at the dimer–dimer interface, can kinetically stabilize the tetramer and modulate amyloidogenicity. (5,6) Accurate measurement of both subunit exchange kinetics and ligand binding stoichiometry is therefore critical for elucidating the TTR dynamics and stability.

Affinity or sequence tags are widely employed in protein expression, purification, or detection. (7,8) While these tags are often assumed to be inert, their influence on protein structure and dynamics are rarely examined in detail. (9,10) Protein tags at the N- and C-terminus of TTR have been shown to have differing gas phase stabilities from those of WT-TTR. (11) The C-terminus is of particular interest because this region participates in the dimer–dimer interface that governs tetramer stability. (11,12) Characterizing how the C-terminal tag (CT) (-ASGENLFYQ) affects TTR’s solution stability and ligand binding is not only relevant for understanding TTR dynamics but also provides an example of how expression tags can alter protein dynamics. (13)

Native mass spectrometry (nMS) has been invaluable for characterizing protein complexes, (14) yet conventional nMS often struggles with heterogeneous samples where overlapping charge state distributions and adduct heterogeneity limit resolution and quantitation. (15) Charge detection mass spectrometry (CDMS) addresses these limitations by independently measuring the charge and m/z of individual ions, enabling the direct determination of molecular mass and abundance. Development of CDMS has largely focused on achieving higher mass resolution (16) and extending measurements toward assemblies into the GDa range. (17,18) However, there is untapped utility for CDMS experiments other than mass and proteoform determination. Jordan et al. showed the capability to assess conformational heterogeneity of mAb aggregates using the added charge dimension that CDMS provides. (19) The current work demonstrates that CDMS can separate proteoforms with overlapping m/z values based on charge and quantify their relative abundances in complex mixtures. While nMS is already a highly quantitative technique, our results establish CDMS as an equally powerful tool for quantitative analysis in heterogeneous systems. (20,21)

Here, we apply Orbitrap-based CDMS/Direct Mass Technology (DMT) using the selective temporal overview of resonant ions (STORI) approach (22,23) to quantitatively compare WT-TTR and CT-TTR, focusing on two biologically relevant properties: tetramer stability assessed via subunit exchange kinetics and ligand-binding affinity. Conventional nMS cannot fully resolve the overlapping charge states of WT- and CT-TTR or their ligand-bound states. However, DMT can resolve these species by directly measuring the mass (m/z × charge), enabling quantitation of all proteoforms. The data reveal that the CT tag alters tetramer stability and thyroxine-binding affinity, demonstrating the structural sensitivity of TTR to modifications at its C-terminus. More broadly, this work demonstrates the impact that protein tags can have on native protein interactions and highlights the broader utility of quantitative CDMS for probing heterogeneous biological samples.

Experimental Section

Data Collection

All experiments were conducted on a Thermo Scientific Q-Exactive UHMR with added DMT capabilities (Bremen, Germany). Before DMT, mass spectra were collected at various resolving powers (6–200k) for each sample, with the instrument parameters reported in the Supporting Information (Table S1). For DMT experiments, the trapping gas pressure in the HCD cell was reduced to 0.3–0.8 to attenuate the signal intensity to a single ion level, as well as decreasing the UHV pressure to assist ion retention through the entire transient of Orbitrap analysis. We observed no significant difference between mass spectra collected at various HCD cell pressures (Supporting Information, Figure S1). For DMT collection, automated ion control (AIC) and 100% target density were used with 200k resolving power.

Results and Discussion

CDMS has emerged as a powerful tool for analyzing heterogeneous biomolecular samples, enabling accurate, direct mass determination by simultaneously measuring the charge and m/z for individual ions. While CDMS has been widely applied for qualitative analyses, its potential for quantitative and less than MDa applications remains underexplored. Figure 1A shows the theoretical mass spectrum of WT-TTR (14+ to 16+) and CT-TTR (15+ to 17+) homotetramers, where the two proteoforms become increasingly resolved as the charge states increase (<3900 m/z). Figure 1B zooms in on the 14+ (WT) and 15+ (CT) charge states, highlighting their strong overlap, which prevents accurate deconvolution of the proteoforms by conventional methods. Figure 1C displays theoretical distributions for 0, 1, and 2 T4 bound states of both WT- and CT-TTR tetramers, where <3900 m/z has observable separation between all proteoforms. However, for the 14+ and 15+ charge states of WT- and CT-TTR, respectively, the 0 T4- and 1 T4-bound populations overlap (Figure 1D). Furthermore, commonly adducted species (Na+, K+, and Zn2+) observed in experimental spectra broaden these distributions, making it increasingly difficult to distinguish and deconvolute the proteoforms (see Figure S2). Here, we employ Orbitrap-based CDMS/DMT to overcome this m/z overlap to resolve and quantify hybrid tetramer formation and T4 binding.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 49, 27057–27063: Figure 1. (A) Theoretical mass spectra of WT-TTR and CT-TTR homotetramers. (B) Zoomed-in view of the 14+ WT-TTR and 15+ CT-TTR distributions to show the large overlap of the proteoforms. (C) Theoretical mass spectra of WT-TTR and CT-TTR homotetramers with thyroxine (T4) binding. (D) Zoomed-in view of the 14+ WT-TTR and 15+ CT-TTR distributions where the 0 and 1 T4 have overlapping distributions. These theoretical distributions do not contain any commonly adducted species (Na+, K+, Zn2+), which broaden the distributions and create more overlap even for the proteoforms in the range 3300–3900 m/z (see Figure S2).

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 49, 27057–27063: Figure 1. (A) Theoretical mass spectra of WT-TTR and CT-TTR homotetramers. (B) Zoomed-in view of the 14+ WT-TTR and 15+ CT-TTR distributions to show the large overlap of the proteoforms. (C) Theoretical mass spectra of WT-TTR and CT-TTR homotetramers with thyroxine (T4) binding. (D) Zoomed-in view of the 14+ WT-TTR and 15+ CT-TTR distributions where the 0 and 1 T4 have overlapping distributions. These theoretical distributions do not contain any commonly adducted species (Na+, K+, Zn2+), which broaden the distributions and create more overlap even for the proteoforms in the range 3300–3900 m/z (see Figure S2).

Thyroxine Binding to TTR Homotetramers

Thyroxine is the less active form of a thyroid hormone important for metabolism that binds to TTR for transport throughout plasma and cerebral spinal fluid. (31) Turnover of T4 into T3 (active) occurs after dissociation, where it can then modulate gene expression via binding to nuclear receptors. (32) The TTR tetramer gains substantial stability as it binds up to 2 T4 at the tetramer interface, decreasing tetramer dissociation and SUE. (33) This has been shown previously to decrease the amyloidogenic rate of TTR, which led to tafamidis (similar in structure to T4) to be designed and is currently the only drug that is approved for clinical treatment of TTR amyloidosis. (34) Measuring the difference in binding affinity between TTR proteoforms may provide insight into regions of TTR or TTR intermolecular/intramolecular interactions that are important for binding of small molecules such as tafamidis and T4.

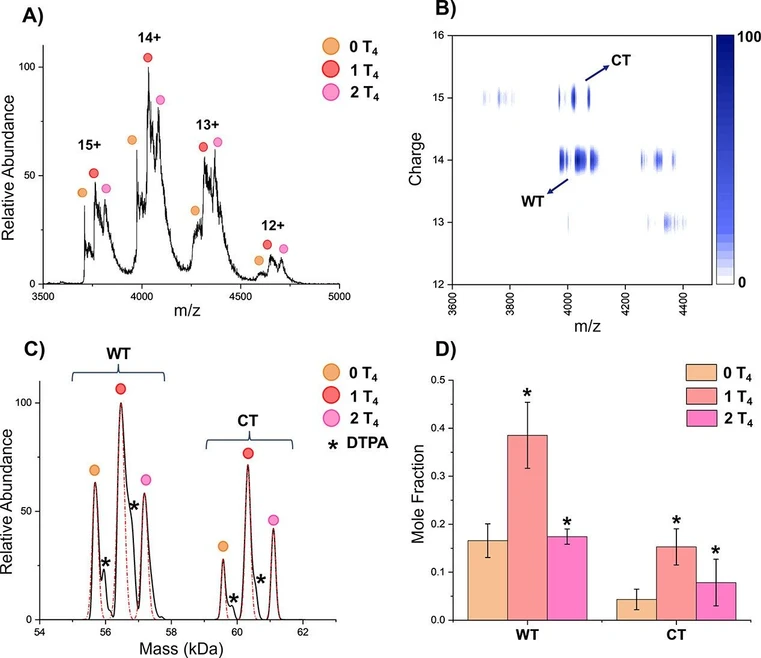

DMT was further applied to quantify T4 binding to WT- and CT-TTR homotetramers, highlighting the technique’s utility in probing protein–ligand interactions. Figure 3A shows a representative mass spectrum of TTR homotetramers in the presence of T4. While ligand-bound species can be observed, homotetramers cannot be confidently resolved across the entire 3000–5000 m/z range. By leveraging the charge-resolving capabilities of DMT, we achieve separation of the homotetramers (Figure 3B,C) and the 0, 1, and 2 ligand-bound states. The 2D plot clearly shows the gain in resolution achieved when charge is simultaneously measured with m/z by separating the 14+ and 15+ charge states for WT and CT, respectively, in the range 3900–4200 m/z. Additionally, using ion mobility does not provide the same kind of 2D resolution due to the similarity in arrival times for the homotetramer proteoforms, as evidenced by Figures S4 and S5 (see the Supporting Information). These data provide evidence that when ion mobility is able to separate out species that overlap in m/z yet differ in mobility, CDMS could be an alternative or used complementarily since the species likely also differ in charge.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 49, 27057–27063: Figure 3. (A) Mass spectra of WT-TTR and CT-TTR homotetramers with thyroxine binding. Ligand binding can be resolved, but homotetramers cannot be confidently identified. Charge states labeled are for WT; CT is always one charge state higher at the same m/z range. (B) DMT heatmap resolving WT-TTR and CT-TTR homotetramers with the additional measurement of charge. (C) Deconvoluted mass spectrum from DMT analysis. Both homotetramers and their ligand binding are resolved, and fit for analysis is shown in red. (D) Mole fraction of each homotetramer and their thyroxine binding species. Error bars represent the standard deviation of replicates (n = 3). The significance for each ligand state is in respect to the left adjacent state. *p < 0.05.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 49, 27057–27063: Figure 3. (A) Mass spectra of WT-TTR and CT-TTR homotetramers with thyroxine binding. Ligand binding can be resolved, but homotetramers cannot be confidently identified. Charge states labeled are for WT; CT is always one charge state higher at the same m/z range. (B) DMT heatmap resolving WT-TTR and CT-TTR homotetramers with the additional measurement of charge. (C) Deconvoluted mass spectrum from DMT analysis. Both homotetramers and their ligand binding are resolved, and fit for analysis is shown in red. (D) Mole fraction of each homotetramer and their thyroxine binding species. Error bars represent the standard deviation of replicates (n = 3). The significance for each ligand state is in respect to the left adjacent state. *p < 0.05.

Conclusion

This work demonstrates that quantitatively, Orbitrap-based CDMS/DMT can determine differences in protein-complex stability and ligand binding. By directly comparing WT- with CT-TTR, we show that the CT tag accelerates tetramer dissociation while enhancing T4 binding affinity. These results indicate that the C-terminus, located at the dimer–dimer interface, plays a more significant role in TTR stability and ligand recognition than previously appreciated. (12) Even the addition of a short peptide sequence perturbs noncovalent interactions at the interface, likely altering solvent accessibility, and the dynamics of the thyroxine binding channel. (37,54) Such findings underscore the importance of evaluating how seemingly minor sequence modifications, such as affinity tags, can influence fundamental biophysical properties.

Beyond TTR, this work positions quantitative CDMS as a broadly applicable strategy for analyzing heterogeneous protein systems, where charge domain separation overcomes the resolution limits of m/z domain measurements in traditional nMS experiments. While much of the field has emphasized extending CDMS to ultrahigh masses and maximal resolution, (16,18) our results highlight the underexplored potential of applying the method in the 1000–10,000 m/z range common to nMS experiments. This capability is directly relevant to heterogeneous membrane protein complexes, which often display broad distributions of oligomeric states, PTMs, lipid, and ligand adducts that complicate spectra. (48,55) Similarly, mAbs can oligomerize and exhibit mass heterogeneity from variable glycosylation, affecting pharmacokinetics, effector function, and stability. (19) CDMS may resolve and quantify such proteoforms in a single experiment without the need for charge reduction or chemical derivatization. (48,56,57)