Solving the retention time repeatability problem of hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography

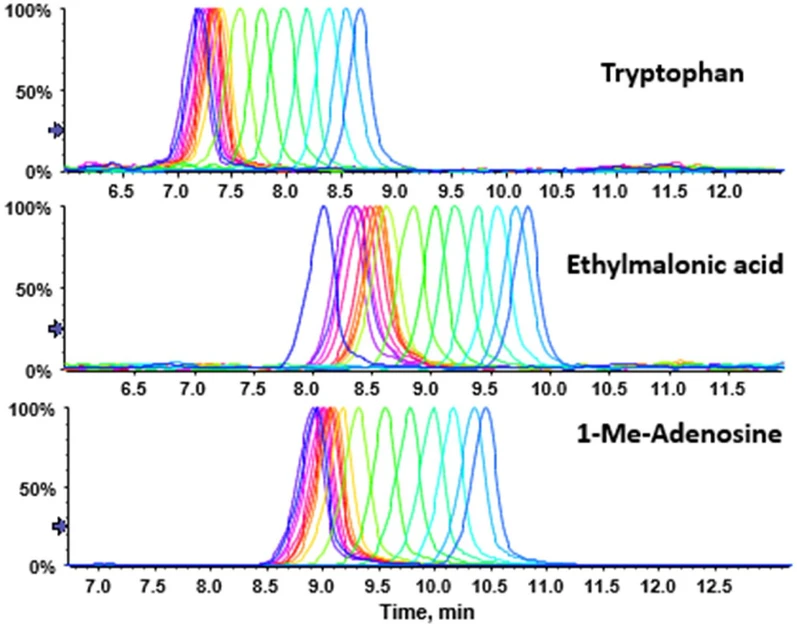

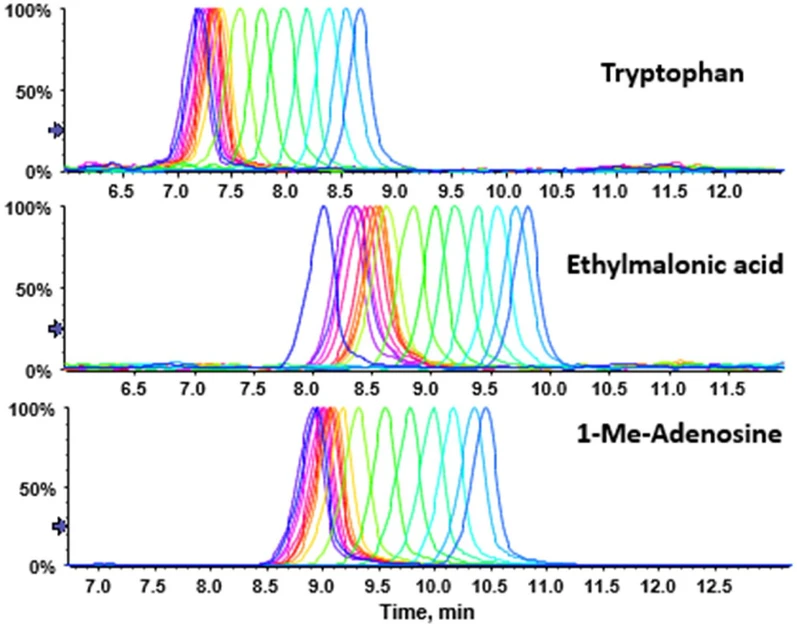

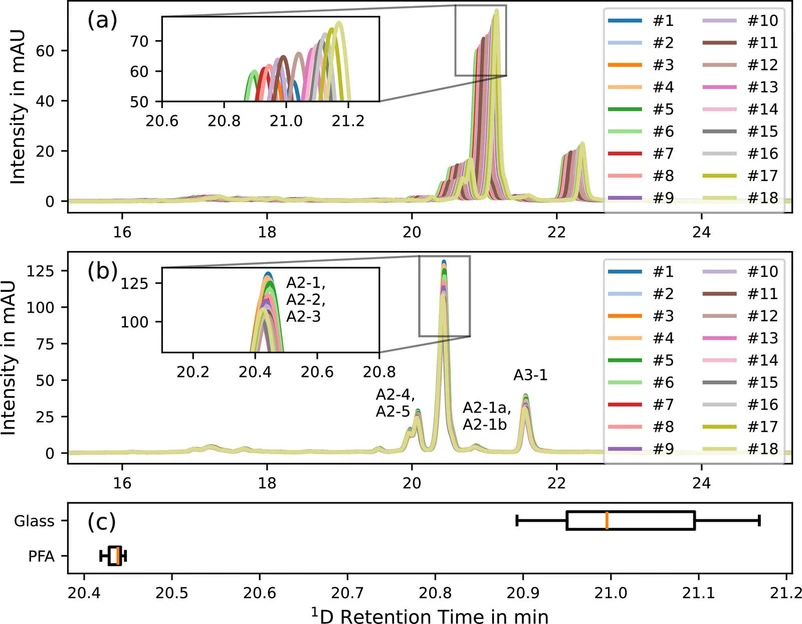

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1730, 16 August 2024, 465060: Fig. 1. Representative chromatograms of test solutes from successively injected metabolomics urine QC samples measured over 12 h (n = 30) with mobile phase stored in (Duran) borosilicate glass bottles. Blue to red colour shift represents n = 1 to n = 10, red to yellow n = 10 to n = 23, yellow to green-blue n = 23 to n = 30. Pattern follows the trend that with progressive injection time an increase in retention time is observed (for corresponding retention time data see Table S2 of the supplementary material).

This study investigates the retention time repeatability issues in hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) and identifies ion release from borosilicate glass solvent bottles as a key factor. These ions alter the semi-immobilized water layer on the polar stationary phase, causing shifts in retention times. By replacing borosilicate glass bottles with perfluoroalkoxy (PFA) bottles, retention time repeatability improved drastically from 8.4% RSD to 0.14% RSD for metabolites over 30 injections in 12 hours.

The study further confirmed similar improvements for peptides and oligonucleotides, demonstrating that solvent bottle material significantly influences HILIC performance. This simple yet effective solution could enhance the acceptance of HILIC in metabolomics, peptide, and oligonucleotide analysis, making it more reliable for both targeted and untargeted studies.

The original article

Solving the retention time repeatability problem of hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography

Kristian Serafimov, Cornelius Knappe, Feiyang Li, Adrian Sievers-Engler, Michael Lämmerhofer

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1730, 16 August 2024, 465060

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2024.465060

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

1. Introduction

Reversed-phase HPLC has become the preferred analytical technique for the analysis of organic molecules in fields like pharmaceutical and food analysis [1,2]. Besides excellent resolving power for molecules differing in lipophilicity, it provides robust and highly repeatable separations. However, highly polar molecules like metabolites, small hydrophilic peptides and oligonucleotides are often not sufficiently retained and separated. For this reason, hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) is the favorable technique nowadays for hydrophilic analytes. The term HILIC has been coined by Andrew Alpert and he showed already in his landmark paper from 1990 that it has exceptional selectivity for amino acids, peptides, oligonucleotides, carbohydrates, organic acids, bases and metabolites [3]). It alleviates precolumn derivatization for enabling RPLC separation and makes the addition of MS-contaminating ion-pairing agents unnecessary [4,5]. The exceptional power of HILIC in various fields including metabolomics has been demonstrated in numerous studies and reviews [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. Part of the great success of HILIC is a wide choice of distinct, nowadays also stable HILIC stationary phases with wide flexibility in the surface chemistry and hence selectivity. According to the ionic character of the functional group being present on the stationary phase surface they can be classified either as neutral phases (amide, diol), charged phases (amino, silica) or zwitterionic phases (e.g., sulfobetaine-modified) [17]. As orthogonal separation principle to RP, HILIC is also of high interest in multidimensional liquid chromatographic separations [[18], [19], [20]].

While the fundamentals of HILIC retention mechanisms look complicated, practice of HILIC has put forth numerous advantages such as excellent selectivity for hydrophilic compounds, good peak shapes, higher sensitivity in ESI-MS, and so forth [23]). In spite of many successful HILIC separations, HILIC has still a poor reputation. Various authors reported poor run-to-run repeatability in HILIC [30]. Tacitly, it is often assumed that the repeatability problem arises from slow column re-equilibration in gradient HILIC. For this reason, several authors performed rigorous studies on partial and full re-equilibration in HILIC as a potential solution to the problem [22,23,31,32]. In particular for metabolomics (addressing a majority of acidic metabolites), other authors suggest the use of anion-exchange chromatography (hyphenated with mass spectrometry via suppressor technology) to overcome the repeatability problem observed in HILIC-based metabolomics [33,34]. Comparison of HILIC-MS and anion-exchange-suppressor-ESI-MS (AEX-MS) by McCullagh and coworkers provided significantly less retention time variance for AEX-MS compared to HILIC-MS [33]. Analytical methods, in which ion concentrations are critical, are typically using plastic bottles as eluent reservoirs, like in ion-chromatography or ICP-MS to avoid background ion contamination. Hence, it might be supposed that in above cited AEX-MS experiments by McCullagh plastic bottles were used for the eluent and borosilicate glass bottles, which are standard for HPLC instruments, for HILIC. Indeed, there is an application note from Agilent Technologies which recommends the used of Nalgene FEP bottles for the mobile phase reservoirs in HILIC in order to avoid the negative effect of sodium ions [35]. However, no comparison with borosilicate glass bottles was shown and this application note may not be known to a wider community of HILIC users.

For this reason, the objective in this work is to elucidate the effect of using plastic (PFA) instead of borosilicate glass bottles for HILIC experiments. Retention time repeatability of polar metabolites (in untargeted urinary metabolomics), peptides and oligonucleotide test samples was documented for bringing the advantage of plastic bottles in HILIC separations to the attention of a wider community of researchers. A discussion of the observed effects with interpretation in view of HILIC mechanisms is given.

2. Experimental

2.2. Metabolomics and oligonucleotide instrumentation

LC-MS analysis of metabolites in urine and of oligonucleotides was performed using an Agilent 1290 Infinity I series LC system from Agilent Technologies (Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a binary pump, thermostated column compartment and an HTC-xt PAL (CTC Analytics AG, Zwingen, CH) autosampler hyphenated to a TripleTOF 5600+ mass spectrometer with DuoSpray Source, operated in TurboIonSpray mode, from Sciex (Ontario, Canada). The LC system was coupled to a Sciex CDS (calibrant-delivery-sytem) for mass calibration. All analytical hardware was standard and not equipped with biocompatible flow path.

2.3. Peptide analysis instrumentation

LC-UV chromatograms were acquired using an Agilent Technologies 1290 Infinity II 2D-LC system. The system consisted of two 1290 Infinity II High Speed (binary) pumps (G7120A), a 1290 Infinity II Multisampler (G7167B), two 1290 Infinity II Multicolumn thermostat compartments (G7116B), a 1290 Infinity II diode array UV absorbance detector (G7117B) and three 1290 Infinity II Valve Drives (G1170A). Both pumps were utilized with the 100 μL JetWeaver. A Max-Light Cell (G4212–6008) with 10 mm path length and V(σ) = 1 μL was used. The flow cell of the 1D UV detector was protected by a pressure relief kit (G4236–60,010). Valve drives were equipped with two deck valve heads and an ASM valve head (G4243A, G4242A) to enable Multiple-Heartcutting (MHC) 2D-LC or Selective Comprehensive 2D LC (sLCxLC) with 40 μL sample loops. In addition, column selector valve heads (G4234C) were installed in both Multicolumn thermostat compartments implementing the option for column screening. The 2D-LC system was coupled to a Sciex CDS (calibrant-delivery-sytem) and further to a Sciex TripleTOF 5600+ system with DuoSpray source electrospray-ionization. All analytical hardware was standard and not equipped with biocompatible flow path. The 2D-HPLC system was operated using Agilent OpenLab CDS ChemStation Edition Rev.C.01.10 and the mass spectrometer was controlled by Sciex Analyst TF 1.8.1.

3. Results

3.1. Retention time repeatability of metabolites in urinary metabolomics analysis

A pooled human urine sample (pooled urine QC sample) was subjected to gradient HILIC-MS analysis by untargeted SWATH-MS detection once with common borosilicate glass bottles and once with PFA bottles as solvent reservoirs for both A and B channel. The sample was injected 30-times (n = 20) over a period of 12 h for each glass and PFA bottles. It allowed to extract chromatograms of numerous metabolites of different physicochemical character in terms of ionization state (anionic, cationic, zwitterionic) and hydrophilicity range (log D at mobile phase pH) to cover a wide molecular space. Fig. 1 shows overlays of representative chromatograms of tryptophan, ethylmalonic acid, and 1-methyl-adenosine recorded with the glass bottles. It can be seen that with the borosilicate glass bottles there is a significant drift of retention from the first injection to the last injection regardless what is the analyte character. Table S-2 gives the statistics for the retention time distributions of representative analytes with glass bottles used during analysis. It can be seen that in all cases evaluated the drift in retention leads to longer retention times and the chemical properties of the selected metabolites (acidic, basic or zwitterionic) play no crucial role in the drift pattern, as the phenomenon observed is identical.

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1730, 16 August 2024, 465060: Fig. 1. Representative chromatograms of test solutes from successively injected metabolomics urine QC samples measured over 12 h (n = 30) with mobile phase stored in (Duran) borosilicate glass bottles. Blue to red colour shift represents n = 1 to n = 10, red to yellow n = 10 to n = 23, yellow to green-blue n = 23 to n = 30. Pattern follows the trend that with progressive injection time an increase in retention time is observed (for corresponding retention time data see Table S2 of the supplementary material).

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1730, 16 August 2024, 465060: Fig. 1. Representative chromatograms of test solutes from successively injected metabolomics urine QC samples measured over 12 h (n = 30) with mobile phase stored in (Duran) borosilicate glass bottles. Blue to red colour shift represents n = 1 to n = 10, red to yellow n = 10 to n = 23, yellow to green-blue n = 23 to n = 30. Pattern follows the trend that with progressive injection time an increase in retention time is observed (for corresponding retention time data see Table S2 of the supplementary material).

3.3. Repeatability in oligonucleotide analysis

HILIC is gaining increasing interest for the separation of oligonucleotide and it was of interest whether retention time repeatability can be improved for this type of solutes as well. The antisense (single) strand of the siRNA Patisiran (the API of Onpattro) was employed as test sample. The repeated injection (n = 7) on the HILIC Amide column showed a mean tR of 5.824 (±0.043) min corresponding to 0.738 % RSD for the borosilicate glass bottles and a mean tR of 5.794 (±0.016) min corresponding to 0.276 % RSD for the PFA bottles (Fig. 5). Again, a significant improvement of tR-repeatability can be observed with the PFA bottles also for oligonucleotides. However, for the tested oligonucleotide the retention drift is different than for the other analytes: Retention time decreases with increasing injection order. It is also noticeable that the peak area declines with every injection, both for glass and PFA bottles. It may be related to the fact that glass (instead of plastic) inserts to vials were used for the sample and only ultrapure water to dissolve the analyte. Possibly, more oligonucleotide adsorbs to the glass wall the longer the sample is standing. Analyses with glass bottles were performed first which explains the smaller peaks for the PFA bottles. It is further striking that the overlaid curves in Fig 4B with the PFA bottles look like a loading study with perfect match of the rear end of the peaks as commonly observed in adsorption isotherm measurements following the Langmuir model. If we omit the two first injections with the PFA bottles, after which the concentration does not change much anymore, the retention time repeatability is even better, i.e. a mean tR of 5.803 (±0.003) min was observed corresponding to 0.054 % RSD. This confirms that PFA bottles are also advantageous for HILIC of oligonucleotides.

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1730, 16 August 2024, 465060: Fig. 4. Representative chromatograms of successively injected teicoplanin test sample solution and comparison of PFA vs glass bottles. (a) UV chromatogram with (Duran) borosilicate glass bottles, shift to higher retention times. (b) UV chromatograms with PFA, no shift. (c) Boxplot shows better repeatabibility for PFA bottles.

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1730, 16 August 2024, 465060: Fig. 4. Representative chromatograms of successively injected teicoplanin test sample solution and comparison of PFA vs glass bottles. (a) UV chromatogram with (Duran) borosilicate glass bottles, shift to higher retention times. (b) UV chromatograms with PFA, no shift. (c) Boxplot shows better repeatabibility for PFA bottles.

4. Conclusion

In this study, retention time repeatability under gradient HILIC conditions (Premier BEH Amide column) was thoroughly investigated using three different sets of analytes (urinary metabolites, peptides, and oligonucleotides). The effect of standard borosilicate glass bottles and PFA bottles as the mobile phase storage vessels on retention time drifts was compared. It became evident that retention time shifts are significant when borosilicate bottles are employed. For the polar metabolites and the peptides, a shift pattern towards stronger retention with increasing analysis time was observed. In contrast, for the oligonucleotide sample the opposite trend was found, i.e. lower retention with higher injection number. It was hypothesized that release of sodium, potassium, borate and other species from the borosilicate glass leads to changes in the semi-immobilized water layer structure and thickness at the interface of the HILIC stationary phase. The altered phase ratio and electrostatic screening effects may lead to shifted retention times compromising retention time repeatability in (gradient) HILIC. This phenomenon can easily be circumvented by use of plastic bottles as solvent reservoirs. Herein, we used PFA bottles instead of borosilicate glass bottles for the eluents. Retention times of urinary metabolites, peptides and oligonucleotides were highly reproducible with RSDs < 0.2 %. PFA is resistant to common HPLC solvents and additives (TFA), highly pure and does not contaminate the ion source. It is a simple solution to replace borosilicate by PFA bottles to solve the commonly reported HILIC retention time repeatability problem. Further improvements in repeatability are envisaged if solvents with even better quality e.g. electrochemical grade are employed which are not supplied in glass bottles but plastic containers. However, for cost reasons it was not considered herein. Future research should also have a look into the effect of aging of the glass bottles and its effect on retention time repeatability addressing the question whether in aged glass bottles the release of ions levels off after a certain time. Moreover, it could be interesting to study the effect of integrating an ion suppressor between pump and injector which removes sodium and potassium cations or a borate ion trap column as suggested recently for improving peak shapes in carbohydrate analysis of some analytes such as mannose [51]. If these strategies along with the use of glass bottles solve the retention time repeatability problem as well, it would be an indirect confirmation for the above hypotheses.