Occurrence of Pharmaceuticals and Other Anthropogenic Compounds in the Wastewater Effluent of Arctic Expedition Cruise Ships

Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2025, 12, 5, 648–654: Graphical abstract

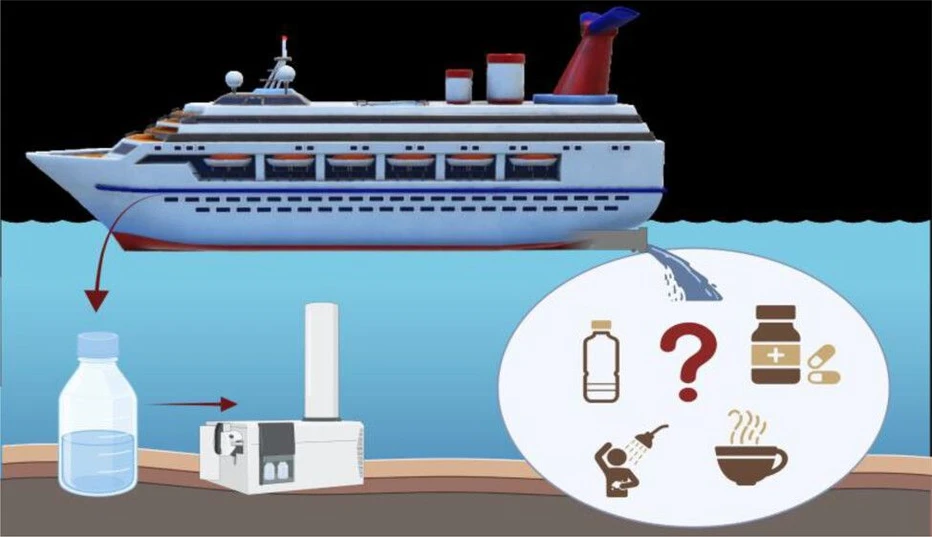

The goal of the study is to investigate the presence of pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and industrial chemicals in treated wastewater discharged from expedition cruise ships operating in polar regions. As cruise traffic increases in these sensitive environments, there is a growing concern over the release of contaminants of emerging concern.

By analyzing samples from three ships using LC-HRMS and data-dependent acquisition, the study identified over 160 compounds, including multiple antibiotics and cardiovascular drugs. The findings highlight the potential for cruise ship effluent to contribute to environmental contamination and the spread of antibiotic resistance, emphasizing the need for further research and regulatory attention.

The original article

Occurrence of Pharmaceuticals and Other Anthropogenic Compounds in the Wastewater Effluent of Arctic Expedition Cruise Ships

Veronica van der Schyff*, Marek Stiborek, Zdeněk Šimek, Branislav Vrana, Verena Meraldi, Andrew Luke King, Lisa Melymuk

Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2025, 12, 5, 648–654

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.5c00209

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Cruise ships discharge wastewater generated from onboard activities. Many ships have advanced wastewater treatment systems (WWTS) onboard. Passenger ships produce graywater (drainage from dishwashers, galley sinks, showers, laundry, baths, and washbasins) and blackwater (from toilets, sanitary areas, and areas with animals). The volume of graywater discharged by cruise ships in 2023 was estimated to be 14 billion L, a 40% increase from 2014 to 2023, largely driven by the growing number of cruise ships. (11)

According to the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) Annex IV, (12) treated blackwater may be discharged more than 3 nautical miles (NM) from the nearest land. Untreated blackwater may be discharged more than 12 NM from land, as the high seas are considered to be capable of assimilating blackwater through natural bacterial action. (12) Similarly, the Polar Code states that untreated blackwater should be discharged more than 12 NM from land, fast ice, or ice shelf, and treated wastewater >3 NM. (13) There are currently no global regulations on the emission of graywater. (14) Depending on the onboard WWTS, gray- and blackwater can be discharged separately or together. The Baltic Sea is currently the only “special area” under MARPOL Annex IV. There, the discharge of untreated blackwater is strictly prohibited by passenger ships, and where possible, ships are expected to discharge blackwater at ports with reception facilities. (15)

Conventional terrestrial-based WWTS do not eliminate all chemical compounds, and treated effluent contains a complex mix of organic and inorganic micropollutants that are then released into the environment. (16−18) This limitation likely extends to ship-based WWTS, particularly given their faster processing times and space constraints compared to terrestrial systems. As with the general population, cruise passengers and crew take medication and excrete metabolites into wastewater, with a potential impact on marine environments. (19) A particular concern is the release of antibiotics, which can promote the development of antibiotic-resistant microbes. (4,5) In addition, ship wastewater may contain other compounds like surfactants, personal care products, plasticizers, and flame retardants, which are often persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic to biota. (4) Ocean currents can transport these contaminants from their point of release to remote areas, potentially affecting sensitive regions and ecosystems. Arctic regions are especially vulnerable to pollution since the efficiency of the naturally occurring bacterial decay of organic contaminants in seawater is slowed by low temperatures. Other environmental factors such as sea ice and fluctuating ultraviolet light exposure due to large seasonal variation also impact pollutant accumulation patterns in the Arctic. (20,21)

With the number and passenger capacity of cruises increasing, it is unclear whether dilution remains sufficient to mitigate the impact of contaminants released from wastewater, particularly in regions with a high density of cruise ships. Pharmaceuticals and other chemicals have been detected in seawater in remote Arctic regions. (20,22) While substandard WWTS in remote Arctic regions are considered the main source of contaminants, (23) other studies (24,25) suggest that the effects of ship effluent should also be studied as a source of pollution.

Limited attention has been paid to wastewater effluent discharges of cruise ships. To the best of our knowledge, only two studies have quantified synthetic compounds in treated wastewater, (4,26) and no chemical screening has been conducted on treated wastewater intended for offshore discharge from cruise ships while in operation. This study aims to identify organic contaminants associated with wastewater discharge from cruise ships as a first step to better evaluate the impact of contaminant emissions from cruise ships on sensitive marine environments.

Methods and Materials

LC-HRMS Analyses and Data Processing

In brief, high-resolution mass spectrometry was used for qualitative analyses of the wastewater extracts. Two aliquots per ship were analyzed. Chromatographic separation was performed using an Agilent 1290 Infinity LC System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) equipped with a Kinetex Core–Shell Biphenyl column (150 mm × 2.1 mm, particle size of 1.7 μm) and a precolumn (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). Mass spectrometry detection was performed by using an Agilent 6550 Q-TOF iFunnel System operating in positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI) modes. Iterative data-dependent acquisition (DDA) of MS/MS spectra was applied, with a maximum of four precursor ions fragmented per cycle at collision energies of 10, 20, and 40 eV. A detailed description of the analytical method is presented in the Supporting Information.

Combined full-scan and MS/MS raw data files were processed with Agilent MassHunter Qualitative Analysis Software 10.0 (Agilent Technologies). Data processing included peak picking, molecular formula assignment, isotope pattern scoring, and identification of the found features based on compliance with the predicted molecular formula and MS/MS spectra present in mass spectrum libraries. A full list of databases used and quality assurance is included in the Supporting Information. All compounds reported here were identified at confidence level 1 or 2 according to the Schymanski identification confidence levels (SL1, confirmed a with reference standard, or SL2, probable structure; library match or diagnostic evidence) in high-resolution mass spectrometric analysis. (28)

Results and Discussion

Wastewater samples from the older ships built in the 2000s (ships 1 and 2) had >11 000 found features, while the newest ship, ship 3, built 2020, had 7571 (Table S1). From these features, a total of 168 compounds were confirmed at SL1 or the chemical structure was proposed at SL2 in treated wastewater across all three ships: 86, 99, and 78 compounds from ships 1–3, respectively (Figure 1 and Tables S2–S4). Twenty-seven compounds were identified at SL1 or SL2 across all ships (Table 1), with pharmaceuticals and industrial chemicals (10 each) constituting the majority, followed by five food/natural compounds, one pesticide, and one UV blocker. Eight of the 27 compounds common to all ships were identified at SL1 based on external standards (EnviMix, Helmholtz-Centre for Environmental Research (29)), and 19 identified at SL2.

Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2025, 12, 5, 648–654: Figure 1. (A) Number of compounds identified at SL1 or SL2, in three expedition ships showing overlap in the compounds found in wastewater among the three ships and (B–D) distribution and number of confirmed or probable compounds according to use category in wastewater effluent from three expedition ships.

Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2025, 12, 5, 648–654: Figure 1. (A) Number of compounds identified at SL1 or SL2, in three expedition ships showing overlap in the compounds found in wastewater among the three ships and (B–D) distribution and number of confirmed or probable compounds according to use category in wastewater effluent from three expedition ships.

For all ships, pharmaceuticals, primarily cardiovascular medication, dominated in terms of the number of compounds identified at SL1 or SL2 (43–59%), followed by industrial chemicals (21–31%) and natural/food compounds (12–17%) (Figure 1).

Industrial chemicals such as surfactants, lubricants, and cleaning products can originate from onboard operations, or from being incorporated into onboard products, like in the case of flame retardants and plasticizers, with release to dust and transfer to wastewater during cleaning or laundering. (36) Many natural compounds can originate from food preparation and consumption, including some with potential environmental impacts, such as caffeine and aromatic amines, the latter being mutagenic. (37)

The compound group of the highest concern consists of pharmaceuticals due to their potential biological activity at low concentrations. (38) The pharmaceuticals were primarily cardiovascular medications, with the sartan group (losartan, irbesartan, candesartan, and telmisartan) identified at SL1 or SL2 (Table 1) in all three ship wastewater profiles. Other cardiovascular medications, flecainide, and bisoprolol, were also identified in wastewater from all three ships (Table 1). (25) Since the aforementioned medications are persistent and known for incomplete removal, even in typical WWTS, it stands to reason that they should be prominent in wastewater from ships too. (39,40)

There is a significant gap in our understanding of the types of compounds present in ship wastewater discharges. This issue is becoming increasingly urgent as the cruise industry expands, especially in sensitive polar regions, and as sustainable development and tourism become more important priorities. Identification and quantification of pharmaceuticals and industrial compounds can support better environmental risk assessment. Water in shipping lanes and cruising routes should be studied to evaluate the effectiveness of dilution and degradability in marine water, particularly in areas where ships are permitted to discharge wastewater. If needed, sensitive regions should be denoted (in addition to the 3 and 12 NM limits) where wastewater discharges should be avoided. Special emphasis should be placed on compounds consistently identified across multiple vessels, including SSRIs, antibiotics, and other substances that could pose environmental concerns at increased concentrations. Moreover, the mixture effects of the various chemicals found in wastewater should be thoroughly examined, as the combined presence of different pharmaceuticals and industrial chemicals may result in additive or synergistic effects that can intensify their harmful impact on marine ecosystems. (55,56) Current regulations and treatment standards of graywater may need reevaluation as we gain an understanding of the impact of trace organic contaminants on marine systems.