Ion exchange chromatography of biotherapeutics: Fundamental principles and advanced approaches

![<p><strong>Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: </strong>Fig. 7. Schematic representation of the 2D-LC-MS platform used for multi-attribute characterization of adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). In this platform, AAV samples first undergo AEX separation for empty and full capsid measurements. Using the multiple heart-cutting technique, fractions are sequentially transferred to the second dimension. In the 2D, the fractions are subjected to online denaturation and desalting in a trap column, followed by separation using RPLC. Separated fractions are then analyzed by MS for intact mass analysis. Adapted from [140], with permission from the American Chemical Society.</p>](https://lcms.labrulez.com/labrulez-bucket-strapi-h3hsga3/Journal_of_Chromatography_A_Volume_1742_2025_465672_Fig_7_Schematic_representation_of_the_2_D_LC_MS_platform_used_for_multi_attribute_characterization_of_adeno_associated_viruses_AA_Vs_61880b8d0c_l.webp)

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 7. Schematic representation of the 2D-LC-MS platform used for multi-attribute characterization of adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). In this platform, AAV samples first undergo AEX separation for empty and full capsid measurements. Using the multiple heart-cutting technique, fractions are sequentially transferred to the second dimension. In the 2D, the fractions are subjected to online denaturation and desalting in a trap column, followed by separation using RPLC. Separated fractions are then analyzed by MS for intact mass analysis. Adapted from [140], with permission from the American Chemical Society.

The goal of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of ion exchange chromatography (IEX) as a key technique for analyzing biotechnology-derived products such as monoclonal antibodies, mRNA, and AAVs. It first explains the fundamental principles of IEX and its mechanisms for separating charge variants using salt or pH gradients.

The review then highlights recent advancements in IEX applications, including improved selectivity through solvent modifications, increased throughput via ultra-short columns, and integration into multidimensional chromatography systems. It also discusses coupling IEX with powerful detectors like mass spectrometry, ion mobility, and light scattering to enhance characterization of complex biotherapeutics.

The original article

Ion exchange chromatography of biotherapeutics: Fundamental principles and advanced approaches

Mateusz IMIOŁEK, Szabolcs FEKETE, Serge RUDAZ, Davy GUILLARME

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 8 February 2025, 465672

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2025.465672

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Among the various LC modes, ion exchange chromatography (IEX) is a particularly attractive one [23]. Indeed, charge variants of mAbs and related compounds (such as bispecific antibodies, fusion proteins, antibody drug conjugates etc.) have gained considerable attention in the biotherapeutic industry due to their potential impacts on stability and biological activity [24]. Common acidic variants arise from deamidation of asparagine, glycation of lysine, and modification of the degree of sialylation of the glycan structure. Basic variants are often originating from C-terminal lysine truncation, N-terminal pyroglutamate formation, isomerization of aspartate to isoaspartate or formation of a succinimide intermediate [25]. All these different variants can be easily separated from the main species and quantified using IEX. Beyond mAbs and related compounds, IEX is also an effective strategy to characterize cell and gene therapy products. For example, mRNA molecules, composed of several hundred to several thousand nucleotide units, are negatively charged at pH > 3 due to the presence of phosphate groups in their sugar- phosphodiester backbone. As a result, IEX has been widely used at the analytical level to investigate heterogeneity, and verify molecular integrity [[26], [27], [28]], but also to purify mRNA samples. In addition, IEX can be used to determine the full/empty capsid ratio of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector-based gene therapy products, as the separation of DNA containing and DNA missing capsids is driven by differences in their isoelectric points directly impacting the relative surface charges [29,30].

The aim of this review is to provide up-to-date and comprehensive information for anyone interested in the characterization of biotechnology-derived products, including mAbs and related compounds, as well as cell and gene therapy products. The review begins with explaining the fundamental principles and retention mechanisms of IEX, and provides some technical solutions to improve selectivity and throughput. Furthermore, the integration of IEX into multidimensional LC setups is discussed, as well as its potential to be coupled with various informative detectors such as MS, ion mobility spectrometry (IMS), and multi-angle light scattering (MALS).

2. Basic principles of IEX and elution modes for biotherapeutics

2.2. pH gradient mode for mAbs characterization

The pH gradient in ion exchange chromatography, achieved by mixing two or more mobile phase components, should ideally be linear, i.e. the pH should be proportional to the composition of the mobile phase. To achieve this, the pKa values of the buffer components must be evenly distributed over the desired pH range [54]. It is important to note that if the stationary phase and buffer ions have the same charge, repulsive interactions can alter the pH near the surface of the stationary phase. The use of zwitterionic buffers is therefore recommended to prevent local pH gradients and maintain a consistent pH throughout the column [54].

In pH gradient mode solutes typically elute in the order of their isoelectric points (pI) or surface charge. However, it is important to note that biomolecules still carry charges at their pI (but the number of positive and negative charges are balanced), which means that they can be either attracted to or repelled from the stationary phase. In addition, not all charged functional groups are available to interact with the stationary phase, making the accessible charge a more accurate predictor of elution order, rather than total charge as indicated by pI [55,56]. Like the salt gradient mode, biomolecules elute in the pH gradient mode according to an on-off retention mechanism [57].

It is often overlooked that an IEX column can significantly influence the apparent mobile phase pH, primarily due to its inherent buffer capacity [58]. Chromatographers typically assume a linear relationship between gradient composition and eluent strength. However, much more complex relationships often arise between gradient input and effluent pH, especially when using MS-compatible mobile phase buffers with low buffer capacity such as ammonium acetate or ammonium carbonate [59]. In this case, the column itself can have unpredictable effects on the effluent pH. The buffering capacity of the column can significantly alter the pH response. The effect of the column on the eluent pH depends on various factors such as the mobile phase/column volume ratio, flow rate, gradient steepness and the buffer capacity of the mobile phase.

If analytes are eluted with a steep and non-proportional pH gradient, the separation may lack selectivity. In this case, all solutes with isoelectric points within the steep effluent pH range will elute in a narrow elution window (high risk of co-elution). Given the importance of pH linearity, it is essential to consider the interplay between the column and mobile phase, and the gradient steepness to column volume ratio. A new approach to correct non-linear pH responses is discussed in Section 3.2.

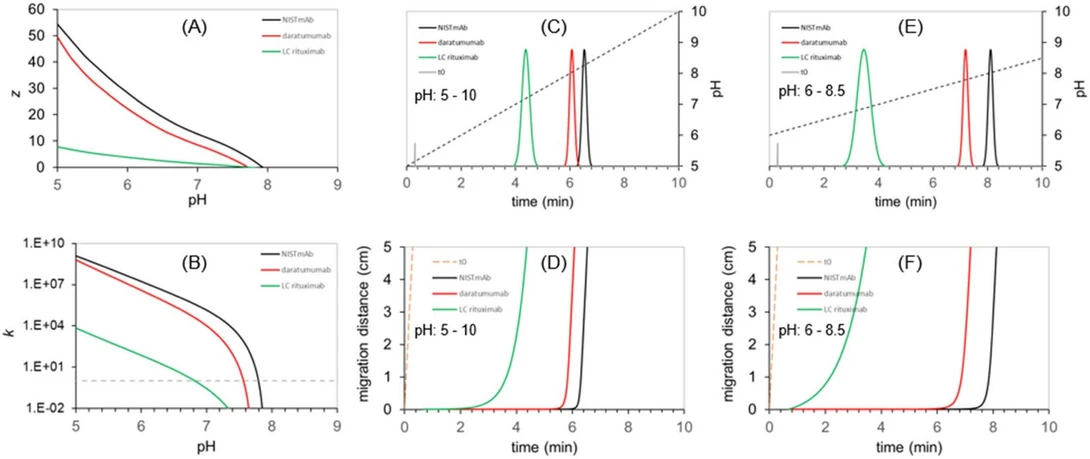

An illustration of the pH gradient elution is shown in Fig. 1. Fig. 1A shows the change in surface charge (z), while Fig. 1B illustrates the expected retention factors (k) for three model solutes (NISTmAb, daratumumab and the light chain (LC) fragment of rituximab) as a function of mobile phase pH. Fig. 1C-D show the corresponding chromatogram and migration distance plots for a pH gradient of 5 to 10 in 10 min, while Fig. 1E-F correspond to a pH gradient of 6 to 8.5 in 10 min. The migration plots suggest that the LC fragment accelerates over time, while the two intact mAbs are either in a "trapped" state (migration distance does not change over time) or in a fully released state (migration distance changes in the same way as the t0 marker indicated on the plots, suggesting no further retention).

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 1. Illustration of pH gradient elution of three test analytes (NISTmAb, daratumumab and the light chain (LC) fragment of rituximab). The model assumes a 2.1 × 50 mm strong cation exchanger column operated at F = 0.25 mL/min and running 10-minute gradients. The expected surface charge (z) and retention factors (k) are plotted as a function of mobile phase pH (A,B). Panel C and E show the chromatograms when running pH gradients 5 – 10 and 6 – 8.5, respectively. Panel D and F illustrates the evolution of solutes’ migration distance in time. (Unpublished data from the authors’ laboratory.).

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 1. Illustration of pH gradient elution of three test analytes (NISTmAb, daratumumab and the light chain (LC) fragment of rituximab). The model assumes a 2.1 × 50 mm strong cation exchanger column operated at F = 0.25 mL/min and running 10-minute gradients. The expected surface charge (z) and retention factors (k) are plotted as a function of mobile phase pH (A,B). Panel C and E show the chromatograms when running pH gradients 5 – 10 and 6 – 8.5, respectively. Panel D and F illustrates the evolution of solutes’ migration distance in time. (Unpublished data from the authors’ laboratory.).

3. Recent advances in IEX

3.1. How to successfully perform a pH gradient method for charge variants analysis of mAbs?

Practicing chromatographers expect proportionality between gradient composition and eluent strength in a chromatographic method. However, this is not necessarily the case when performing a pH gradient in IEX. First, it is not easy to design buffer systems that universally provide a pH response proportional to the mobile phase (buffer) composition. Second, the stationary phase also contributes to the equilibrium constant through its buffer capacity.

For example, as the composition of the gradient changes, the pH may not change linearly or predictably due to the buffer capacity and dissociation constants of the components involved. This can lead to unexpected and irreproducible retention and separation of analytes, which makes method development and optimization difficult. Achieving reliable and reproducible results in a pH gradient often requires careful selection and adjustment of buffer systems, taking into account not only the desired pH, but also how changes in buffer composition will affect the overall phase equilibrium together with the column.

An elegant, simple approach based on empirical correction of the mobile phase gradient program has been recently proposed and successfully applied [67]. As a linear mobile phase gradient is passed through the column, the pH response of the phase system is monitored and recorded. An inverse function of the pH response is then applied to generate a new mobile phase gradient program that provides improved pH linearity (gradient program correction). In fact, only one measurement is required to derive the improved (corrected) gradient program. Although this method is applicable to most columns and buffers, there may be situations in which deviations from linear response are too large to correct. Fig. 3 shows an example of a pH gradient correction based on the inverse function method.

![Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 3. Observed pH response curves (orange) and corresponding charge variant UV profiles (black) of dalotuzumab when running linear (A) and corrected (B) mobile phase (ammonium acetate) gradients. Adapted from [67], with permission from Elsevier.](https://lcms.labrulez.com/labrulez-bucket-strapi-h3hsga3/Journal_of_Chromatography_A_Volume_1742_2025_465672_Fig_3_Observed_p_H_response_curves_da6f32a17e_l.webp) Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 3. Observed pH response curves (orange) and corresponding charge variant UV profiles (black) of dalotuzumab when running linear (A) and corrected (B) mobile phase (ammonium acetate) gradients. Adapted from [67], with permission from Elsevier.

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 3. Observed pH response curves (orange) and corresponding charge variant UV profiles (black) of dalotuzumab when running linear (A) and corrected (B) mobile phase (ammonium acetate) gradients. Adapted from [67], with permission from Elsevier.

4. Multidimensional IEX methods for biotherapeutics

In recent years, IEX has been incorporated into various multidimensional liquid chromatography (mD-LC) setups, offering several benefits: i) enhanced compatibility with MS by using a desalting chromatographic step prior to MS detection, ii) improved resolution due to the use of two orthogonal separation dimensions, and iii) the possibility to perform automated on-line sample preparation and chromatographic analysis simultaneously [[100], [101], [102], [103]]. These advantages are explored in this section.

One of the first attempts to use IEX in mD-LC setup dates back to 2015 [104]. Stoll et al. developed a selective comprehensive strategy combining IEX, RPLC, and MS to thoroughly characterize rituximab and make IEX compatible with MS by incorporating a desalting RPLC step. The choice of a selective comprehensive rather than a fully comprehensive 2D-LC strategy was motivated by the ability to eliminate the under-sampling problem by fractionating the 1D effluent containing analytes of interest into several small fractions rather than a single larger one [[105], [106], [107]]. This selective comprehensive approach allowed focusing on a specific zone of interest in the chromatogram and was easier to implement than a full comprehensive 2D-LC method, since the different fractions can be collected into several loops and reanalyzed afterward. With this method, the different isoforms and subunits of rituximab have been identified with MS, and the common use of high concentrations of non-volatile salts in IEX, was no longer problematic as peaks could be desalted on the RPLC column before high-resolution MS identification. This approach was successfully applied for the characterization of intact rituximab samples, partially digested rituximab (IdeS digestion), and rituximab samples partially digested and reduced (with DTT). A wide range of post translational modifications (PTMs) were observed, including C-terminal lysine truncation, various glycoforms, oxidation, the presence of pyroglutamate residue, among others. In a subsequent study, the same authors used a similar strategy but employed comprehensive IEX x RPLC-MS to compare three reference/biosimilar pairs of mAbs, namely cetuximab, trastuzumab, and infliximab, covering a large range of differences. These experiments were performed at the middle-up level of analysis with fragments ranging between 25 and 50 kDa [108]. The 2D-LC method enhanced the performance of traditional 1D separation techniques by increasing peak capacity and providing detailed information on hydrophobic and charge variants. For cetuximab, 2D-LC effectively separated charge variants, revealing differences in glycosylation and other PTMs. For trastuzumab, it showed clear differences in peak patterns and intensities between samples, enabling the identification of a single amino acid variation in the sequence. Infliximab and its biosimilar, despite high overall similarity, were differentiated by minor glycosylation pattern differences identified through 2D-LC. The group of Rathore et al. developed several 2D-LC workflows involving IEX, allowing enhanced separation and characterization of mAb variants [109,110]. Their first study involved the use of CEX in the first dimension and AEX in the second dimension using a heart-cutting approach [109]. The authors have clearly demonstrated that the 2D method resolved more variants compared to standalone CEX or AEX separations. As an example, for a model mAb product, the 2D method identified 13 variants, while CEX and AEX identified only 10 and 8, respectively. The different variants that were characterized corresponded to modifications like deamidation, oxidation, and isomerization. In another work, Bhattacharya et al. created a comprehensive analytical workflow for mAbs directly from cell culture supernatant, combining protein A affinity chromatography with SEC and CEX, along with MS detection [110]. This method characterized mAb titer, size, charge, and glycoform heterogeneities within 25 min and was validated according to ICH Q2(R1) guidelines. Lambiase et al. introduced an innovative heart cutting 2D-LC/MS approach that combines SEC and CEX for simultaneous profiling of mAb aggregates and charge variants [111]. This method quantified aggregates using SEC in the first dimension, and then transferred the monomer peak via heart-cutting for charge variants analysis using CEX in the second dimension. They developed both a salt-based CEX method with UV detection, and an MS-compatible CEX method, enabling on-line charge variant peak identification. The applicability of the method was proven in a forced degradation study of a mAb candidate, showing significant improvements in overall analysis time (20 min), sample consumption (10 µg required), and degree of automation. This allowed for processing up to 70 samples per day, greatly enhancing high-throughput process development.

Gstöttner et al., later updated by Goyon et al., proposed an even more powerful strategy using a 4D-LC-MS approach for detailed mAb charge variant characterization, involving on-line peptide mapping, and an automated on-line fraction collection [112,113]. The multiple-heart cutting 4D-LC-MS approach allowed to thorough characterization of up to 9 charge variants. As highlighted in Fig. 6, it includes four chromatographic dimensions: 1D-CEX method to separate charge variants, followed by 2D-RPLC to reduce and separate the mAb subunits, 3D with column immobilized trypsin to rapidly perform on-line digestion into peptides and 4D RPLC to achieve peptide separation and identification using high resolution MS. The automated system demonstrated high precision and repeatability, showing similar levels of oxidation and deamidation with fewer artifacts compared to off-line methods. The workflow was tested for different mAbs with various stress conditions, such as oxidation and thermal stress, demonstrating its robustness and versatility. Since then, various researchers have expanded the capabilities of mD-LC setup [[114], [115], [116]], proving its applicability to a wider range of molecules such as bispecific antibodies. mD-LC has evolved significantly and is now applied to various complex mAbs and related products, potentially becoming a process analytical technology (PAT) tool for real-time monitoring of mAb quality during biomanufacturing [117]. Recent mD-LC workflows have integrated different chromatographic modes and sample preparation steps to allow comprehensive characterization at multiple levels (intact, reduced, and peptide).

![Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 6. Schematic representation of the automated 4D-LC-MS workflow, enabling (i) the separation and fractionation of charge variants by CEX, (ii) on-column reduction and sub-unit analysis by RPLC, (iii) trypsin digestion in flow through mode, (iv) peptide mapping analysis by RPLC and hyphenation to MS. Adapted from [113], with permission from Elsevier.](https://lcms.labrulez.com/labrulez-bucket-strapi-h3hsga3/Journal_of_Chromatography_A_Volume_1742_2025_465672_Fig_6_Schematic_representation_of_the_automated_4_D_LC_MS_workflow_042c0cfa8f_l.webp) Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 6. Schematic representation of the automated 4D-LC-MS workflow, enabling (i) the separation and fractionation of charge variants by CEX, (ii) on-column reduction and sub-unit analysis by RPLC, (iii) trypsin digestion in flow through mode, (iv) peptide mapping analysis by RPLC and hyphenation to MS. Adapted from [113], with permission from Elsevier.

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 6. Schematic representation of the automated 4D-LC-MS workflow, enabling (i) the separation and fractionation of charge variants by CEX, (ii) on-column reduction and sub-unit analysis by RPLC, (iii) trypsin digestion in flow through mode, (iv) peptide mapping analysis by RPLC and hyphenation to MS. Adapted from [113], with permission from Elsevier.

Besides mAbs, the 2D-LC-MS platform has recently been used to characterize AAVs which are increasingly popular gene therapy vectors. In this work, the authors developed a heart-cutting 2D-LC-MS method using AEX in the first dimension to separate empty (E) and full (F) AAV capsids and to measure the F/E ratio. In the second dimension, RPLC-MS was employed to separate and characterize viral proteins (VP1, VP2 and VP3) constituting the AAV, along with their isoforms, with modifications such as clipping or phosphorylation. In this setup, a trap column was essential between the two dimensions for online denaturation and desalting, improving viral proteins separation and removing MS-incompatible salts. The setup is shown in Fig. 7. This method was successfully applied for the high-throughput multi-attribute characterization of AAV8 samples, with minimal sample handling required.

![Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 7. Schematic representation of the 2D-LC-MS platform used for multi-attribute characterization of adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). In this platform, AAV samples first undergo AEX separation for empty and full capsid measurements. Using the multiple heart-cutting technique, fractions are sequentially transferred to the second dimension. In the 2D, the fractions are subjected to online denaturation and desalting in a trap column, followed by separation using RPLC. Separated fractions are then analyzed by MS for intact mass analysis. Adapted from [140], with permission from the American Chemical Society.](https://lcms.labrulez.com/labrulez-bucket-strapi-h3hsga3/Journal_of_Chromatography_A_Volume_1742_2025_465672_Fig_7_Schematic_representation_of_the_2_D_LC_MS_platform_used_for_multi_attribute_characterization_of_adeno_associated_viruses_AA_Vs_61880b8d0c_l.webp) Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 7. Schematic representation of the 2D-LC-MS platform used for multi-attribute characterization of adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). In this platform, AAV samples first undergo AEX separation for empty and full capsid measurements. Using the multiple heart-cutting technique, fractions are sequentially transferred to the second dimension. In the 2D, the fractions are subjected to online denaturation and desalting in a trap column, followed by separation using RPLC. Separated fractions are then analyzed by MS for intact mass analysis. Adapted from [140], with permission from the American Chemical Society.

Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 1742, 2025, 465672: Fig. 7. Schematic representation of the 2D-LC-MS platform used for multi-attribute characterization of adeno-associated viruses (AAVs). In this platform, AAV samples first undergo AEX separation for empty and full capsid measurements. Using the multiple heart-cutting technique, fractions are sequentially transferred to the second dimension. In the 2D, the fractions are subjected to online denaturation and desalting in a trap column, followed by separation using RPLC. Separated fractions are then analyzed by MS for intact mass analysis. Adapted from [140], with permission from the American Chemical Society.

6. Conclusion

As highlighted in this review paper, IEX is a highly informative and mature technique for characterizing biotechnology-derived products. It is often considered a native chromatographic mode, thus preserving the integrity of the molecules analyzed. Compared to other non-denaturing LC modes such as HIC, SEC, or affinity-LC, IEX - in most cases - offers higher resolving power and unique charge-based selectivity. However, developing IEX methods is often more challenging, with multiple elution methods including salt-gradient, pH-gradient, salt-mediated pH gradient or ion-pairing salt gradient conditions. IEX is applicable to a wide range of biotechnology-derived products, including protein-based and nucleic-acid-based ones, such as mAbs and related compounds, or gene therapy products.

Some interesting approaches have been recently suggested to enhance the selectivity and throughput of IEX, such as using step/multi-step gradients, adding organic solvents or ion pairing agents to the mobile phase, employing shorter columns of only a few millimeters in length, or automated screening of conditions. While these technical solutions are still maturing, their popularity is expected to increase in the future. The integration of IEX into mD-LC setups and its coupling with MS further increase its analytical power and are anticipated to see broader adoption.

These recent developments make IEX a strong and flexible tool, capable of handling ever more complex biotherapeutic constructs. IEX will continue to be a key technique in the analysis of newly developed products, contributing to consistent quality control and thorough characterization.