Rapid Multi-Omics for Bacterial Identification Using Flow Injection–Ion Mobility–Mass Spectrometry

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 26, 13809–13816: Graphical abstract

Mass spectrometry has accelerated bacterial identification in clinical microbiology, but protein-based methods often struggle with species-level resolution. Lipid- and metabolite-based MS approaches offer improved specificity, including detection of antibiotic resistance traits.

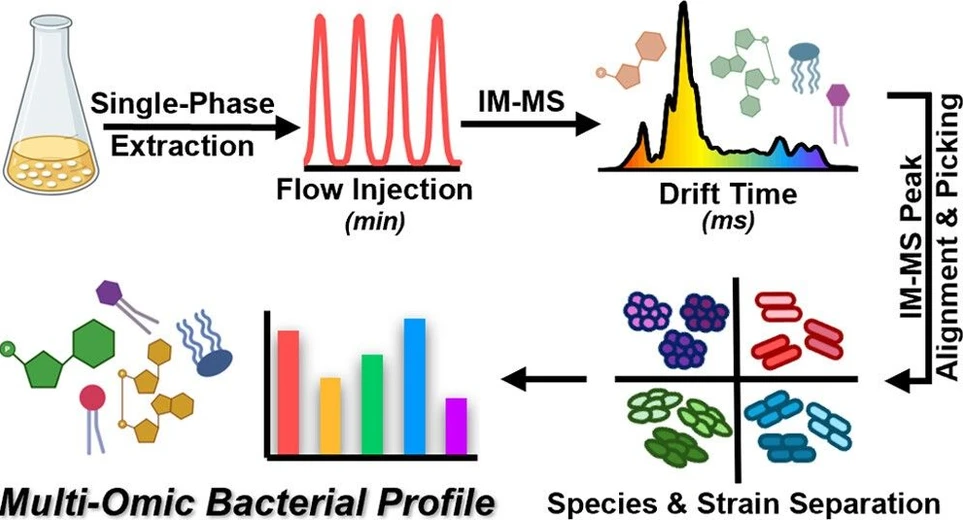

In this study, we applied rapid flow-injection ion mobility mass spectrometry (FI-IM-MS) to characterize bacterial pathogens. By replacing liquid chromatography with ion mobility separation, we achieved simultaneous detection of lipids and metabolites, distinguishing 24 ESKAPE strains. FI-IM-MS matched the performance of LC-IM-MS while reducing analysis time from 17 to 2 minutes per injection. The stability of the IM dimension supports its use for quantitative peak analysis. These findings highlight the potential of rapid multi-omics to enable strain-level identification and resistance detection in clinical microbiology.

The original article

Rapid Multi-Omics for Bacterial Identification Using Flow Injection–Ion Mobility–Mass Spectrometry

Hannah M. Hynds, Jana M. Carpenter, Kelly M. Hines*

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 26, 13809–13816

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.5c00417

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

The investigation of a class of biomolecules and their corresponding biological processes, known as omics, has gained growing attention in the past decade due to its significant correlation with the causation and progression of disease states. While single-omic techniques like genomics, (1−3) transcriptomics, (4) and proteomics (5−7) have provided comprehensive profiles of individual biomolecular groups, it has been demonstrated that the combination or integration of multiple omic techniques yields a more comprehensive understanding of the biological systems under investigation. (8,9) A typical multiomics study breaks down biological samples into separate biochemical components, analyzes each type of biomolecule separately, and then integrates the resulting data sets using advanced bioinformatics strategies. While the knowledge gleaned from these experiments is exceptionally insightful, the time and resource requirements for the analytical and informatic pipelines typically limit the use of multiomics approaches to mechanistic or discovery-type studies.

One area that could benefit from rapid multiomic strategies is clinical microbiology, where mass spectrometry has become the standard method for the identification of unknown bacterial species. Platforms like the bioMérieux Vitek MS and Bruker Biotyper rely on protein fingerprint spectra that are generated by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization and time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF-MS) to differentiate bacteria at the genus and species level. (10−15) Other strategies that are in development target differences in lipids between bacterial species. MALDI-ToF-MS and similar approaches have been used to detect glycolipids, (16−19) fatty acids, (20−22) and phospholipids, (23,24) while direct sampling strategies like the MasSpec Pen, (25) paper spray, (26−28) or rapid evaporative ionization MS (REIMS) (29−31) rely mostly on phospholipids, fatty acids, and other lipophilic molecules. Other MS-based bacterial identification strategies incorporate liquid chromatography with MS to measure the signature metabolites that are produced and consumed by different bacteria. (32,33) While each of these methods have shown success in identifying bacteria based on a subset of the organism’s biomolecular composition, it is reasonable to expect that gains in the specificity or sensitivity of bacterial identification could be improved by using a multiomics approach to detect differences across several classes of biomolecules. However, the implementation of multiomics at the speed and scale required for diagnostic settings like clinical microbiology requires a significant improvement in the throughput of the multiomics strategy.

An alternative strategy to the standard multiomics workflow would be to forego the initial partitioning of the biological sample and preserve its inherent “multiomic” composition from the start. From an analytical perspective, there are several reasons why this would be a difficult approach to implement─first among them being the incompatible chemical properties (i.e., solubility, polarity, etc.) of the biomolecules themselves. Other difficulties, such as ionization suppression and interferences, can be addressed to some extent with liquid chromatography, but solubility issues still limit the breadth of chemical complexity that is feasible in samples for chromatographic separations. On the other hand, gas-phase separations based on ion mobility (IM) provide some capability to resolve similar mass or isobaric analytes that differ in their structures. The combination of IM with MS (IM-MS) presents the additional advantage of biomolecular-specific trendlines that arise from differences in the relationships between size and mass across lipids, metabolites, peptides/proteins, etc. (34−36) Although IM drift times vary between instruments, the calibration or normalization of drift times to collision cross sections (CCS) provides a stable molecular descriptor that can be shared across laboratories or IM instruments and used as evidence for the identification of unknown ions.

We have previously demonstrated the feasibility of hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) and IM-MS to resolve four representative Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria based on the simultaneous analysis of lipids and metabolites from single-phase extracts. (37) However, the redundancy of the class-level separation in the HILIC and IM dimensions suggests that one pre-MS separation dimension may be sufficient for the analysis of bacterial lipids and metabolites. Examples of rapid IM-MS measurements without chromatographic separations have been achieved by others using sample introduction strategies like paper spray (PS) (26,27) and flow injection (FI). (38−41) These studies have primarily focused on narrow subsets of biomolecules, such as metabolites or lipids, and have not investigated the impact of these sample introduction strategies on the overall performance relative to methods that use chromatographic separations. Here, we perform a side-by-side comparison of HILIC-IM-MS and FI-IM-MS for strain-level differentiation in six types of bacteria based on their multiomic profiles. Our study demonstrates that FI-IM-MS can achieve the same quality of data as HILIC-IM-MS in a fraction of the time. The ability to perform rapid analyses of bacterial lipids and metabolites, enabled by IM-MS and FI, represents a positive step toward the development of multiomic methods that have the speed and throughput required for clinical microbiology and other diagnostic areas.

Experimental Methods

Ion Mobility–Mass Spectrometry

Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) and flow injection (FI) were coupled to the electrospray ionization source of a Waters SYNAPT XS traveling wave ion mobility mass spectrometer (TWIM-MS) for data collection. Sample introduction methods and mass spectrometry settings can be found in Document S1. All collision cross section (CCS) calibration methods and results can be found in the Supplemental Experimental Methods section of Document S1. Details on the components and concentrations of the CCS calibration mixtures can be found in Document 2. Data were analyzed using Water’s Driftscope, Progenesis QI, and EZInfo. For FI-IM-MS data, Driftscope was used to collapse the retention time dimension and export the corresponding drift time dimension or arrival time distribution. An example of the resulting IM-MS data, arrival time distribution, and representative extracted mobilograms are shown in Figure 1. Progenesis QI was then used for both FI-IM-MS and HILIC-IM-MS data sets to import, peak pick, align, normalize, and visualize the data. All data were normalized to the OD readings during the bacterial growth process (Document S2). The data were then filtered by ANOVA p-value or by feature intensity before being exported to EZInfo for principal component analysis (PCA). Student’s t-test p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. (42) The raw HILIC-IM-MS and FI-IM-MS data files are available in the MassIVE data repository (MSV000097587). Additional information on the identification of lipid and metabolite features using accurate mass and CCS can be found in Document S1.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 26, 13809–13816 - Figure 1. FI-IM-MS (ESI+) data from multiomic mixture containing P. aeruginosa strain NR-51529. (A) Ion mobility–mass spectrometry conformational space. From the ion mobility dimension, (B) the total 1D ion mobilogram and extracted ion mobilograms for (C) pyocyanin, (D) nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, and (E) phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) 34:1 are shown.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 26, 13809–13816 - Figure 1. FI-IM-MS (ESI+) data from multiomic mixture containing P. aeruginosa strain NR-51529. (A) Ion mobility–mass spectrometry conformational space. From the ion mobility dimension, (B) the total 1D ion mobilogram and extracted ion mobilograms for (C) pyocyanin, (D) nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, and (E) phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) 34:1 are shown.

Results and Discussion

Precision of FI-IM-MS versus HILIC-IM-MS

Before evaluating the ability to distinguish bacterial species, we first investigated the precision of the FI-IM-MS method relative to our previously demonstrated HILIC-IM-MS approach. Precision was evaluated using the IM-extracted peak areas of features detected in replicate injections of a pooled quality control (QC) sample that contained a mixture of extracts from each strain evaluated. As seen in Figure 2A,B, FI-IM-MS data collected for 16 QC injections over a 5-h period cluster tightly in the PCA score plots without any need for filtering. The relative standard deviation (%RSD) of FI-IM-MS features with peak intensities greater than 50 was calculated. This threshold retained 80% (1481/1736) and 85% (1394/1739) of the total detected features from positive and negative ionization modes, respectively. As seen in Figure 2C,D, 79% and 90% of the retained FI-IM-MS features had RSDs below 15% in positive ionization mode and negative ionization mode, respectively. These data demonstrate that the FI-IM-MS method and particularly the IM dimension from which peak areas were extracted provide high-precision measurements for complex biological extracts in a short analysis time.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 26, 13809–13816: Figure 2. PCA plots of (A) positive and (B) negative mode FI-IM-MS data from 16 injections of a pooled QC and 96 bacteria extracts. RSDs calculated based on (C) 1481 features in ESI+ and (D) 1394 features in ESI– that were detected in all QC replicates with an intensity ≥50.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 26, 13809–13816: Figure 2. PCA plots of (A) positive and (B) negative mode FI-IM-MS data from 16 injections of a pooled QC and 96 bacteria extracts. RSDs calculated based on (C) 1481 features in ESI+ and (D) 1394 features in ESI– that were detected in all QC replicates with an intensity ≥50.

For comparison, we performed the same evaluation on LC-extracted peak areas of features detected in 10 replicate injections of QC collected throughout the HILIC-IM-MS experiment. The combination of a 17-min HILIC separation with IM-MS provides a higher peak capacity than the 2 min FI-IM-MS method, and therefore more features were detected in the HILIC-IM-MS data set. (43,44) The same intensity threshold of 50 retained 38% (4165/10953) and 20% (1434/7080) of the respective positive and negative mode HILIC-IM-MS features. Although the percentage retained is smaller, this filtered HILIC-IM-MS data set still represents a similar magnitude of features (1× for negative mode and 3× more for positive mode) compared to the FI-IM-MS data set. As shown in Document S1, Figure S3, just 60% of the positive mode HILIC-IM-MS features and 54% of the negative mode HILIC-IM-MS features had RSDs below 15%.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that the IM-MS strategy for multiomics can achieve species- and strain-level separations for representative strains of the ESKAPE pathogens with an analysis time of 2 min per injection. The FI-IM-MS approach has proven to provide results comparable to those of a previous method for simultaneous lipid and metabolite measurements in bacteria, which was based on a 17-min HILIC-IM-MS method. Although the FI-IM-MS method is more susceptible to ionization suppression, we have demonstrated that the impact of ionization suppression on an easily ionized metabolite is similar between FI and HILIC. The large number of overlapping features and strong positive correlations for the raw abundances of identified lipids and metabolites between the two data sets further demonstrates that the FI-IM-MS approach can achieve similar performance to the HILIC-IM-MS method, but in a fraction of the time. Collectively, these results represent a promising first step in the development of rapid IM-MS-based multiomics as a platform for bacterial identification. Future work will require the curation of databases containing multiomic bacterial signatures and the establishment of scoring algorithms that can be used to identify unknown bacterial isolates. We expect that IM-MS-derived CCS values will be critical in ensuring that bacterial identifications are based on accurately annotated features.