Source Fingerprinting of PFOA via Full- and Intramolecular Stable Isotope Ratios of Carbon Using Orbitrap-IRMS

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 50, 28028–28036: Graphical abstract

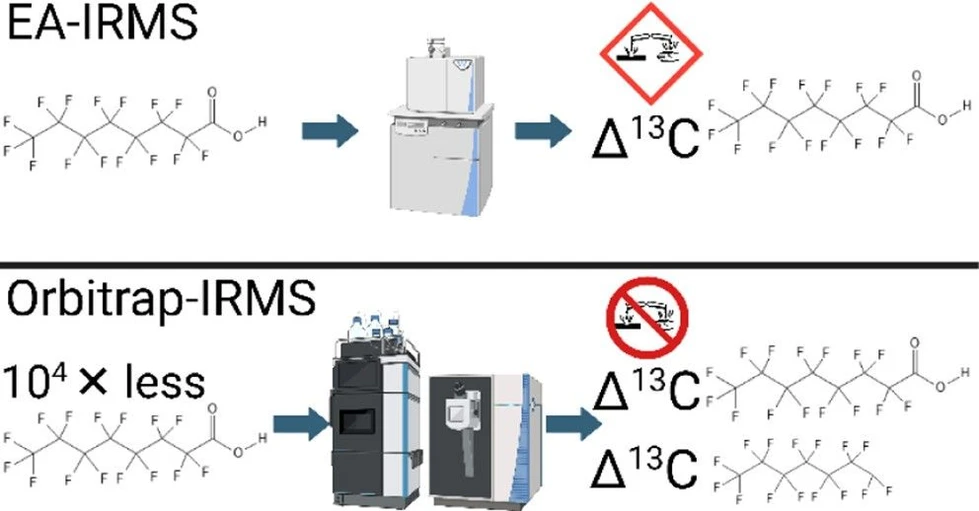

Source attribution of PFAS contamination requires analytical tools capable of distinguishing compounds at trace levels. This study introduces an electrospray ionization Orbitrap-IRMS approach for determining stable carbon isotope ratios of PFAS without analyte decomposition or HF formation, overcoming key limitations of conventional magnetic sector IRMS.

Using perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) as a model compound, full-molecule and intramolecular isotope ratios were measured across 23 commercial samples from multiple suppliers. The combined isotopic signatures provided strong discrimination between samples and correlated with synthesis routes, demonstrating the potential of Orbitrap-IRMS as a forensic tool for PFAS source fingerprinting in environmental studies.

The original article

Source Fingerprinting of PFOA via Full- and Intramolecular Stable Isotope Ratios of Carbon Using Orbitrap-IRMS

Holden M. Nelson, Zhiliang Xu, Hui Li, and James J. Moran*

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 50, 28028–28036

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.5c06168

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) make up a broad class of synthetic organofluorine compounds that have been mass-produced since the 1950s. As surfactants with high thermal and chemical stability, PFAS are incorporated into a wide range of industrial and consumer products, including fire-fighting foams, nonstick cookware, and fast-food packaging, among many others. (1−6) Their prevalence in an expansive array of goods and industrial processes has led to the near-ubiquitous occurrence of PFAS in ecosystems around the globe. (7−12) This, combined with documented and predicted health consequences from even trace PFAS exposure, has propelled PFAS to the forefront of many environmental efforts, with a focus on reducing PFAS exposure and developing remediation strategies for cleaning up PFAS contamination. (13−15) Gauging the success of remedial efforts requires tools for monitoring PFAS provenance and transport in the environment. Current environmental forensic methods for PFAS contamination primarily rely on the use of chemical and isomeric fingerprints. (16) Standard methodologies for testing PFAS concentrations only detect a limited set of congeners, and the prevalence of a limited number of different congeners across multiple industries can result in suspected sources sharing a chemical signature. (17) Major synthesis pathways of PFAS compounds generate isomerically distinct products, with fluorotelomerization producing linear-only isomers, whereas other methods, such as electrochemical fluorination (ECF) and liquid-phase direct fluorination (LPDF), generate some branched isomers in addition to the primarily linear product. (18) However, the resolving power of isomer ratios can only be used to distinguish between the two different synthesis pathways, and there is currently not sufficient evidence to suggest that two distinct sources of PFAS compounds produced by the same method can be reliably differentiated by this method alone. (19)

Stable isotope ratios can provide critical source attribution insights for environmental pollutants, including hexachlorocyclohexanes, (20) organophosphorus pesticides, (21) and other halogenated organic compounds. (22) Variations in intrinsic stable isotope ratios can be imparted by the method utilized to synthesize a compound and differences in the isotope ratios of precursors, providing complementary potential to discriminate the origin of pollutants beyond what chemical and isomeric content can provide alone. While magnetic sector isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) is the traditional workhorse for stable isotope measurements, there are two key limitations to using IRMS for PFAS analysis. First, elemental analyzer IRMS measurements of common PFAS congeners require ∼1 mg of analyte per analysis, (23) an unrealistically high quantity in environmental samples where even trace amounts of PFAS pose an environmental concern. Second, IRMS requires complete conversion of the analyte into a simple gas prior to ionization─a challenge for PFAS compounds due to both the stability of the carbon–fluorine bonds and the resultant HF produced, which can damage the instrument.

Although IRMS-based stable isotope analysis of PFAS may be untenable, emerging techniques in high-resolution mass spectrometry offer an alternative approach. (24) The ability of Orbitrap-IRMS to measure isotope ratios in inorganic and organic compounds has recently been demonstrated across a variety of applications. (24−27) In comparison to IRMS, Orbitrap requires smaller sample sizes (pico- to nanomoles versus micromoles C) per analysis. Also, Orbitrap-IRMS measurements can be performed using electrospray ionization (ESI) (28)─circumventing the otherwise requisite combustion/oxidation step. Further, Orbitrap-IRMS allows for measurements of intramolecular isotope ratios via analysis of ion fragments generated in the ESI source. (27) The implementation of intramolecular stable isotope analysis has historically been reliant on the use of site-specific natural isotopic fractionation nuclear magnetic resonance (SNIF-NMR) (29) and pyrolysis gas chromatography IRMS (py-GC-IRMS). (30) Recent studies have shown great potential with NMR-based isotopic analyses of organofluorines. (31) However, like magnetic sector IRMS, SNIF-NMR requires significantly more sample than is feasible for most field sampling of PFAS compounds, with analyses typically requiring milligrams of analyte per measurement. Pyrolytic techniques, much like other chemical processes to convert analytes to simple gases, produce HF as a reaction byproduct, making it impractical for intramolecular isotopic analyses of PFAS.

Here, we sought to test whether Orbitrap-IRMS could be used to obtain high-precision stable isotope measurements of PFAS compounds, using perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) as a model compound due to its widespread presence at contaminated sites and prominence in the literature. (32) We wanted to further evaluate whether PFOA contains sufficient variation in stable isotopic content to make this a useful intrinsic signature for advancing environmental fingerprinting and source attribution efforts. We describe methodological developments used for stable isotope measurements of both PFOA and a decarboxylated fragment of PFOA, and discuss the ability to use stable isotope analysis to fingerprint these samples.

2. Methods

2.2. UHPLC-Orbitrap-IRMS Parameters

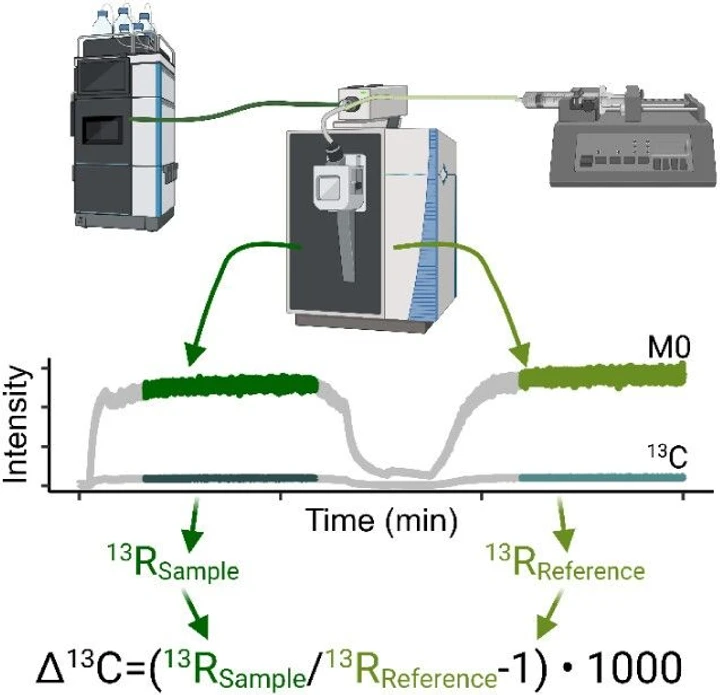

We performed stable carbon isotope measurements of PFOA using a Vanquish Neo ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatograph (UHPLC; Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to an Orbitrap Exploris 240 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). We used an OptaMax NG electrospray ionization source with an HESI LOFLO needle insert. Instrument and probe parameters are shown in Table 1. For each analysis, 50 μL of 1.0 mg L–1 analyte was introduced into a 25 μL sample loop and injected into the Orbitrap over a 14.5 min window. No chromatographic columns were utilized, allowing for continuous introduction of analyte to the Orbitrap. To prevent sample broadening, we set an initial flow rate of 10 μL min–1 for 1 min and then dropped the flow rate to 3 μL min–1 to begin sample analyses. Over the course of a sample analysis, we applied a gradient flow rate from 3 μL min–1 to 2.75 μL min–1. After this, the introduction flow path was changed using a six-port valve, allowing a reference PFOA-01 solution to be injected via a syringe pump at 3 μL min–1 from a 1 mL gastight syringe, as shown in Figure 1. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate, followed by a blank injection of 50:50 acetonitrile/methanol and a standard injection of the reference solution (PFOA-01) via UHPLC. Four samples (PFOA-01, PFOA-04, PFOA-13, and PFOA-21) were analyzed across multiple days to assess the long-term measurement precision of the method. Stable carbon isotope ratios were similarly collected for both ESI-generated [PFOA-H]−1 ions and [PFOA-CO2H]−1 fragment ions. Analysis sequences of [PFOA-CO2H]−1 were performed independently of the [PFOA-H]−1 measurements.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 50, 28028–28036: Figure 1. PFAS samples were injected into the mass spectrometer via an ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatograph, followed by a reference solution injected via a syringe pump. The isotope ratios of the sample and reference were calculated from the intensities of the 13C-substituted ion to the isotopically unsubstituted ion.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 50, 28028–28036: Figure 1. PFAS samples were injected into the mass spectrometer via an ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatograph, followed by a reference solution injected via a syringe pump. The isotope ratios of the sample and reference were calculated from the intensities of the 13C-substituted ion to the isotopically unsubstituted ion.

2.4. Isomeric Analysis

We identified the presence of branched PFOA isomers using a Prominence high-performance liquid chromatography system (HPLC; Shimadzu) coupled to a QTRAP 4500 triple quadrupole-linear ion trap mass spectrometer (SCIEX). A 0.30 mL min–1 flow rate carried an injection volume of 4 μL through the HPLC. A C18 column (50 × 2.0 mm, 5 μm particle size, Gemini) separated linear and branched isomers of PFOA, with samples identified by retention times compared to a calibration standard within ±0.1 min. Phase A of the binary mobile phase consisted of LC-MS grade water (Honeywell) containing 20 mM ammonium acetate (Hampton Research), and Phase B consisted of LC-MS grade acetonitrile (Millipore Sigma Supelco). We set a gradient flow to pre-equilibrate the column with 10% Phase B for 2 min, increased to 60% Phase B from 0.5 to 4.0 min, to 90% Phase B from 4.0 to 7.5 min, and held at this ratio until 10.0 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in negative ionization mode, and PFOA was analyzed using scheduled multiple reaction monitoring mode (sMRM), in which dwell time was optimized to enhance sensitivity. The ion spray voltage was set at 4,500 V and temperature at 600 °C. The declustering potential, entrance potential, collision energy, and collision cell exit potential were set at −35, – 10, −14, and −7 V, respectively. Curtain gas pressure, collision gas pressure, and ion source gas pressure were set at 35, 6, and 50 psi, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

3.3. Isomeric Analyses and Potential Synthesis Insights

As synthetic compounds, PFAS are commonly produced from precursors originating from fossil fuel sources. Methane-based sources of carbon are known to have depleted stable isotopic signatures compared to oil/coal-derived carbon. (38) The combination of isotopic and isomeric signatures in this study indicates that different synthesis methods are associated with different carbon sources. Exclusively linear synthesis of PFOA arises through mechanisms, such as fluorotelomerization, whereas branched isomers are formed through processes such as ECF or LPDF. (18,19) Isomeric analyses of the PFOA samples used in this study showed that, of the samples where the Δ13C[PFOA-H]-1 was greater than −5‰, seven of the nine contained branched isomers, and the remaining two (PFOA-15 and PFOA-24) were exclusively linear. All samples below the −5‰ threshold demonstrated linear-only isomeric patterns. These results track with prior research indicating that more 13C-enriched samples of PFOA tend to show branched patterns, but not exclusively. (23) However, the broad sample set provided in this study shows that isotopically depleted samples are exclusively linear (Table S.D.1, Figures S.D.1 and S.D.2).

These isotopic results are consistent with known precursors for the different synthesis methods. In ECF and LPDF, an octanoyl halide is reacted with HF or F2 to produce PFOA. (39) Octanoyl halides are often produced from octanoic acid, which is often industrially produced from octanol. Octanol is commonly produced via one of two processes: 1) the hydroformylation and oxidation of petroleum-derived 1-heptene, or 2) through the Ziegler-Alfol process, which reacts four ethenes together in the presence of Al, H2, O2, and water. (40,41) In fluorotelomerization, small perfluorinated ethene monomers react to form longer, straight-chain PFAS, where ethene, in turn, is often industrially produced from Fischer–Tropsch reactions with primarily natural gas-derived carbon monoxide. (32,42) The enriched isotopic signatures indicate that manufacturers utilizing branched-isomer-producing PFOA synthesis processes favor the use of the longer-chain petroleum-derived precursors, whereas the isotopic depletion of the linear isomers indicates that manufacturers using fluorotelomerization often source their precursor materials from methane-derived carbon (Figure 4, Table S.C.1). The two PFOA samples with enriched isotopic signatures and exclusively linear isomers could indicate that carbon monoxide used in forming the perfluorinated ethenes originates from incomplete combustion of petroleum or coal.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 50, 28028–28036: Figure 4. A schematic shows the potential movement of carbon through the synthesis process. Arrows can indicate multiple reaction steps, with prominent intermediates shown. The isotopic signature of a product is reflective of the source material, where methane is typically more depleted in 13C compared to oil/coal sources.

Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 50, 28028–28036: Figure 4. A schematic shows the potential movement of carbon through the synthesis process. Arrows can indicate multiple reaction steps, with prominent intermediates shown. The isotopic signature of a product is reflective of the source material, where methane is typically more depleted in 13C compared to oil/coal sources.

4. Conclusion

Our method utilizes the Orbitrap-IRMS method for the stable isotopic analysis of carbon in PFAS compounds in environmentally relevant quantities. Isotopic characterization of PFOA fragments allows for measurements of intramolecular stable carbon isotope ratios, increasing forensic resolving power. Future work should evaluate the impact of multi-isotopic measurements on source attribution potential─incorporating oxygen isotope ratio measurements in addition to carbon to better distinguish between samples. Further, continuing to develop analyses for smaller fragments of PFOA to better understand the intramolecular isotopic composition of the compound would allow for improved differentiation between different sources. Given the vast array of PFAS compounds currently dispersed throughout the environment, extending Orbitrap-IRMS measurements to other congeners would allow for broader applicability of this method to sites not containing PFOA and improved resolution of PFAS sources from environmental samples. An Orbitrap-IRMS analysis of PFOA consumes ∼50 ng of PFOA per analysis. Median concentrations of PFOA in contaminated soils are between 38 and 83 ng g–1, (48) which would enable an Orbitrap-IRMS analysis via extraction of PFOA from 1 g of soil. In drinking water, where the current EPA maximum contaminant limits (MCL) are set to 4 ng L–1 for PFOA, (49) a sample of water at this level or higher would require 12.5 L to isolate enough PFOA for an Orbitrap-IRMS analysis (assuming 100% extraction recovery). This demonstrates a feasible approach compared to EA-IRMS, which would require complete extraction of PFOA from 12,000 to 26,000 g of soil for one replicate analysis or 250,000 L of contaminated water with PFOA at 4 ng L–1 MCL. This Orbitrap-IRMS method lays a foundation for extending current stable isotopic methodologies of environmental contaminants─such as for source attribution and remediation monitoring─to PFAS compounds.