Development and thorough evaluation of a multi-omics sample preparation workflow for comprehensive LC-MS/MS-based metabolomics, lipidomics and proteomics datasets

Talanta, Volume 286, 2025, 127442: Graphical abstract

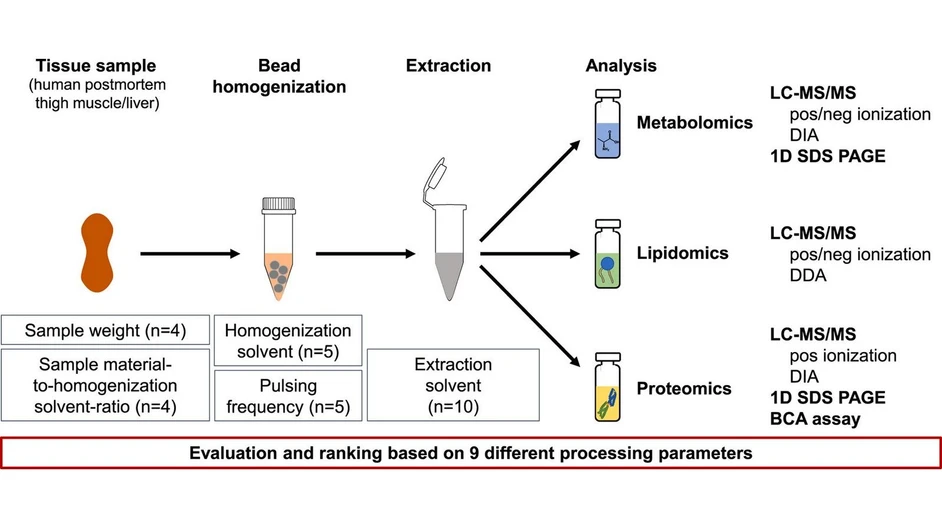

The goal of this study was to systematically evaluate and compare ten different mono- and biphasic solvent extraction methods to optimize sample preparation for untargeted multi-omics analyses—specifically metabolomics, lipidomics, and proteomics—from the same human postmortem tissue samples (liver and muscle). The motivation was to reduce variability and preserve sample integrity by avoiding multiple freeze-thaw cycles and sample splitting.

The researchers also assessed four homogenization parameters and identified an optimal approach involving bead-homogenizing tissue in a Water:Methanol mixture. Using LC-MS/MS, SDS-PAGE, and BCA assays, they comprehensively ranked all protocols and found that monophasic extraction using Methanol:Acetone (9:1) delivered the most complete datasets. This method offers potential for automation and high-throughput workflows, enabling robust multi-omics profiling in clinical research.

The original article

Development and thorough evaluation of a multi-omics sample preparation workflow for comprehensive LC-MS/MS-based metabolomics, lipidomics and proteomics datasets

Lana Brockbals, Maiken Ueland, Shanlin Fu, Matthew P. Padula

Talanta, Volume 286, 2025, 127442

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2024.127442

licensed under CC-BY 4.0

Selected sections from the article follow. Formats and hyperlinks were adapted from the original.

Individual omics studies (e.g. genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, lipidomics, metabolomics) have been used in the last decade for the study of diseases (including biomarker research and drug discovery) or in fields like agriculture, plant sciences and microbiology [1,2]. In recent years, multi-omics workflows have gained popularity to understand links between genotype and phenotype and to generate a more comprehensive/systemic picture of biological and biochemical processes within an organism [3,4]. Multi-omics has previously been defined by Krassowski et al. as “an approach aiming to improve the understanding of systems regulatory biology, molecular central dogma and genotype-phenotype relationship by combining three or more different omics data” [1]. While the integration of multiple omics datasets often requires overcoming extensive computational and data processing hurdles (e.g. combining dimensions of very different outputs from each -omics technique), it is crucial to consider multi-omics method integration during study design and sample preparation/extraction [1,4,5]. In general, the importance of sample preparation selection is often overlooked [6]. Depending on the choice of extraction solvent/method, an extraction bias for certain compounds/compound classes can occur. Metabolomics studies by Canelas et al. and Duportet et al. have previously shown that the same samples extracted with different extraction methods/solvents can result in significantly different measurements of metabolite levels and contradictory biological interpretation of active metabolite pathways [7,8]. This stresses the enormous impact that the choice of sample preparation method/extraction solvent can have on untargeted -omics studies. While a certain level of extraction bias can most likely never be excluded with a simple and rapid extraction workflow, it is crucial to be aware of the limitations of one's sample preparation approach and ideally choose a method that is as unselective and reproducible as possible.

Often for multi-omics studies, collected samples are split into multiple aliquots for -omics specific extraction [[9], [10], [11]]. However, to minimize issues with sample heterogeneity and additional freeze-thaw cycles during sample splitting, multiple -omics datasets should ideally be generated from the same set of samples [5]. For this, frequently biphasic organic solvent systems are used, requiring extensive multi-step protocols to isolate individual compound classes [[12], [13], [14]]. Most common examples of these solvent systems are adaptations of the Bligh-Dyer/Folch- (chloroform, methanol (MeOH) and water) [15,16] or Matyash-extractions (methyl tert-butylether (MTBE), MeOH and water) [17], requiring careful pipetting during phase separations. As a consequence, these workflows are low-throughput and susceptible to sample loss [18]. In general, these extractions usually result in an organic and an aqueous phase along with a protein precipitate, that can be separated out for lipidomics, metabolomics and proteomics analysis, respectively. Historically, however, protein precipitation methods have often been considered unreliable for proteomics analysis and specialized protein extraction was preferred. Nevertheless, due to advancements and more systematic studies, protein precipitation is nowadays well established and one of the most common methods for protein extraction in both bottom-up and top-down proteomic workflows [[19], [20], [21]]. Individual studies have also started to investigate monophasic (all-in-one) extraction procedures, to increase throughput, decrease sample loss and potentially allow automation [18,22].

The aim of the current study was to develop and thoroughly evaluate a multi-omics sample preparation workflow that aids in comprehensive metabolomics, lipidomics and proteomics datasets by comparing and adapting/modifying existing homogenization procedures along with monophasic and biphasic extraction solvent mixtures. The focus was on postmortem human muscle and liver tissue samples. Comparing these two matrices, the aim was also to investigate whether or not a biphasic extraction procedure might be mandatory/advisable to achieve comprehensive lipidomics results for lipid-rich tissue such as liver [23,24].

In total, four homogenization parameters were evaluated along with 10 different mono- or biphasic extraction solvents/mixtures. Selection of the latter were based on adaptations of the classic Bligh-Dyer/Folch and Matyash-extractions along with a variety of all-in-one extraction procedures, such as Boxler et al. [25] and Muehlbauer et al. [18]. For the biphasic solvent mixtures, in addition to the classic 2:1 organic solvent-to-water ratio, a 1:1 mixture (extra water) was trialed, as this was previously suggested to increase the yield of metabolites, while decreasing the amount of lipids extracted within the polar metabolomics phase [23]. Overall, homogenization and extraction parameters were compared and thoroughly evaluated based on untargeted liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)-based metabolomics, lipidomics and proteomics as well as 1D sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay results.

2. Materials and methods

2.3. Liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS) analysis

2.3.1. Metabolomics

The metabolomics fraction of all samples were analysed by an untargeted LC-high resolution (HR) MS method. Data was acquired by data independent acquisition (DIA) using an Acquity M-class LC system (Waters, Milford, MA, US) coupled to a Synapt XS time-of-flight (TOF) MS (Waters, Milford, MS, US). One microliter of sample material was loaded onto a Scherzo SM-C18 column (3 μm particle size, 13 nm pore size, 1 × 150 mm), heated at 40 °C with a flow rate of 75 μL/min. Detailed LC and MS parameters can be found within the supplementary material. All samples were analysed in triplicates in a randomised order. A mix of 27 endogenous reference standards from various compound classes (16 detectable in positive ionization mode, 12 detectable in negative ionization mode, Table S1 and Table S2) was used to monitor system suitability before each run and was the basis for the metabolomics targeted data processing detailed below.

2.3.2. Lipidomics

Only samples comparing the different extraction solvents were analysed with an HRMS-based untargeted lipidomics method. Data was acquired in top-8 data dependent mode (DDA) on an Agilent 1290 Infinity UPLC system (Santa Clara, CA, US) coupled to a Q Exactive Plus orbitrap MS (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, US) with detailed LC-MS parameters summarized within the supplementary material. All samples were analysed once, in randomised order.

2.3.3. Proteomics

In addition to the visualisation and quantification of the protein content using 1D SDS-PAGE and a BCA assay, all samples investigating the extraction solvent, were analysed with an HRMS-based untargeted proteomics method. Based on the quantitative protein results of the BCA assay, 15 μL of sample material (equated to < 10 μg of protein per sample) that was previously resuspended in 50 μL of a 1 % SDC in HEPES solution (containing TCEP and IAA; after heating, centrifugation and incubation detailed above), was incubated with 1 μL trypsin (0.5 μg/μL) at 37 °C for 18 h. The samples were de-salted and cleaned up using STAGE-tips (STop And Go Extraction) following a protocol adapted from Rappsilber et al. as described within the supplementary material [26]. Following evaporation to dryness, the extracts were reconstituted in 25 μL mobile phase A (0.1 % formic acid in water). Data was acquired in DIA mode on an Acquity M-class LC system (Waters, Milford, MA, US), coupled to a Synapt XS time-of-flight (TOF) MS (Waters, Milford, MS, US). Five microliter of sample material was loaded onto a BEH C18 column (1.7 μm particle size, 300 Å pore size, 300 μm × 150 mm) heated at 45 °C with a flow rate of 5 μL/min. Detailed LC and MS parameters adapted from Wang et al. and Distler et al. can be found in the supplementary material [27,28]. All samples were analysed in duplicates/triplicates in a randomised order.

3. Results and discussion

3.2.2. Metabolomics

3.2.2.2. Untargeted

The targeted evaluation of the metabolomics dataset was followed by an untargeted workflow. It has previously been discussed in the literature that the “total number of features” is neither a good quality indicator for an untargeted metabolomics method nor is it a reflection of true positive hits [38]. As it is still one of the most commonly employed parameters for the evaluation of different sample preparation methods and software processing workflows, the total number of features per extraction solvent mixture was still assessed (also taking variability between replicates into account) in this study. This was complemented with an investigation into the number of organic acid compounds extracted per solvent mixture, which was based on feature identification on the compound class level (level 3 identifications according to the metabolomics standards initiative proposed minimum reporting standards [39]).

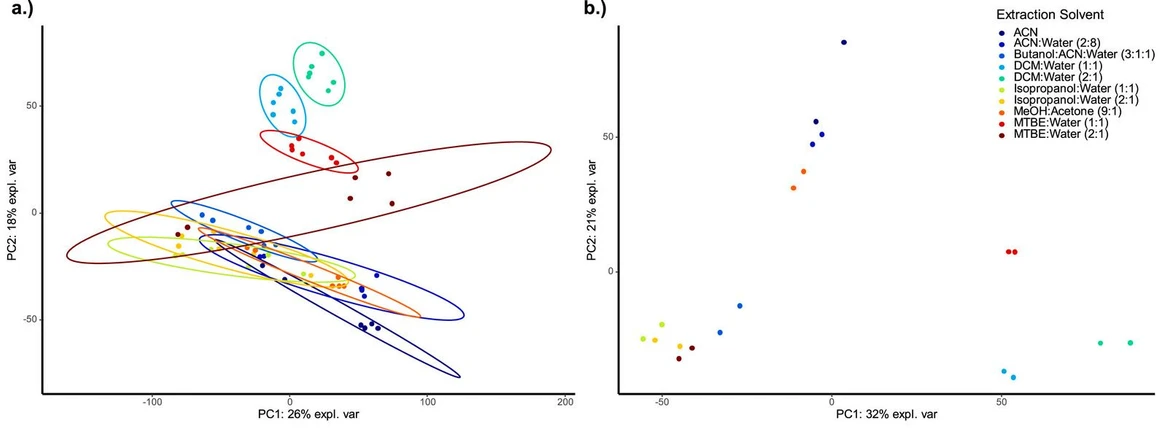

Similar to the targeted processing approach, the variability between replicates was first assessed. Fig. 2a shows the principal component analysis results of all muscle sample replicates (positive ionization) per trialled extraction solvent mixture (n = 6). High variability can be observed for all extraction solvents except for DCM:Water (1:1 and 2:1) and MTBE:Water (1:1). It is striking that for all other extraction solvents, the first technical injection replicate seems to be different to the two remaining injection replicates for each biological sample. A similar behaviour is also visible for the negatively ionized dataset (muscle samples, Fig. S3a) and for the liver samples (both ionization techniques, Figs. S4a and S5a). Although the exact reason for this observed phenomenon is unknown, this could be caused by evaporation effects after piercing the vial lid during the first injection. For the current experiment all three injection replicate injections were carried out from the same vial, however, based on the results it is recommended to use individual aliquots for each technical replicate injection and/or change the pierced lid after injection to prevent extensive solvent evaporation. Cooling of the autosampler tray to 4 °C did not significantly improve this issue. For the monophasic extraction solvents containing only, or a very high proportion of, organic solvents, this phenomenon was expected. This can be alleviated by evaporating the extracts to dryness (e.g. using N2 or a vacuum centrifuge) and reconstituting them in a more aqueous solvent (e.g. the LC method's starting conditions). Particularly for untargeted metabolomics studies, however, sample evaporation always poses the risk of analyte loss, which is why the extracts were directly injected. To look at similarities in extraction behaviour of the tested solvent mixtures, a principal component analysis of the first technical injection replicate was carried out (Fig. 2b; muscle tissues sample, positive ionization mode). Both DCM:Water mixtures (1:1 and 2:1) show a similar extraction behaviour to MTBE:Water (1:1). This indicates that, except for the muscle tissue extraction with MTBE:Water (2:1), all other biphasic solvent mixtures seem to extract similar metabolite patterns, leading to clustering. MTBE:Water (2:1) seems to be more similar to Isopropanol:Water (1:1 and 2:1) and Butanol:ACN:Water (3:1:1) in terms of metabolite extraction. The classic protein precipitation solvents like MeOH:Acetone (9:1), ACN and ACN:Water (2:8) also cluster together indicating similarities in their untargeted metabolomics profile. The general trend for principal component separation between monophasic and biphasic extraction solvents was also clearly visible in negative ionization mode (muscle tissue) and for both ionization modes when extracting liver tissue samples (Figure S3b, S4b and S5b). This could also be caused by the fact that the extracts from the monophasic extractions contain both the metabolomics and the lipidomics fraction for analysis. Although the LC-column used for the metabolomics method favours retention and hence analysis of polar metabolites, the multi-mode column properties might also facilitate analysis of some lipids. In an untargeted data processing workflow, features could therefore also be lipids that contribute to the visual extraction solvent separation. This is also reflected by the number of features extracted. As visualized in Fig. 3a and b and detailed in Table S12, ACN, MeOH:Acetone (9:1), ACN:Water (2:8) and Butanol:ACN:Water (3:1:1) lead to the highest number of metabolomics features extracted in positive ionization mode (both muscle and liver tissue samples; normalized peak area of individual replicates >100). In negative ionization mode, MTBE:Water (2:1) and Isopropanol:Water (1:1 and 2:1) both showed a similar number of features compared to the aforementioned monophasic extraction solvents, with DCM:Water mixtures (1:1 and 2:1) consistently (both ionization modes) extracting the least number of features and hence scoring last for this evaluation parameter (Fig. 3a and b, Table S12). The proposition by Wu et al. [23] that a biphasic extraction might be mandatory for reproducible extraction of lipid-rich tissue such as liver cannot be supported as the monophasic extraction solvents show better results in terms of reproducibility and variety of extracted compounds. While it was already discussed that the total number of features in an untargeted metabolomics experiment is not necessarily a reflector of true positive hits [38], DCM:Water (1:1 and 2:1) was also found to lead to the least number of organic acids and derivatives identified on the compound class level (Table 3). For muscle tissue samples, the top 3 extraction solvents for a comprehensive metabolomics dataset (positive ionization) were MeOH:Acetone (9:1), ACN and ACN:Water (2:8) using both the total number of features and the compound class identification as evaluation parameters. In negative ionization mode, additionally to these extraction solvents, MTBE:Water (2:1), Isopropanol:Water (2:1) and as well as Butanol:ACN:Water (3:1:1) also performed well for either or both evaluated parameters. In the light of the findings by Wu et al. [23] it is surprising that the 2:1 organic solvent-to-water mixtures performed worse than the extraction solvents with a 1:1-ratio for our untargeted metabolomics evaluation. The addition of extra water was previously found to increase the yield of metabolites, which cannot be supported with our current findings. Overall, looking at the compound class identifications seems to be a good complementary evaluation criterion for evaluating extraction solvent differences during method development.

Talanta, Volume 286, 2025, 127442: Fig. 2. Principal component analysis of the untargeted metabolomics data (positive ionization) from muscle samples; underlying data includes all features (raw abundance) with a retention time >1 min and <19 min; a) all biological (n = 2) and injection (n = 3; technical) replicates; b) only injection replicate 1 of both biological replicates; MTBE: methyl-tert-butylether, DCM: dichloromethane, ACN: acetonitrile, MeOH: methanol; PC: principal component.

Talanta, Volume 286, 2025, 127442: Fig. 2. Principal component analysis of the untargeted metabolomics data (positive ionization) from muscle samples; underlying data includes all features (raw abundance) with a retention time >1 min and <19 min; a) all biological (n = 2) and injection (n = 3; technical) replicates; b) only injection replicate 1 of both biological replicates; MTBE: methyl-tert-butylether, DCM: dichloromethane, ACN: acetonitrile, MeOH: methanol; PC: principal component.

Talanta, Volume 286, 2025, 127442: Fig. 3. Boxplots visualizing the number of features extracted with the untargeted metabolomics workflow in positive ionization mode; n = 6 per extraction solvent (2 biological replicates and 3 replicate injections (technical replicates) of these); all relative standard deviations between replicates are <15 %; a) muscle tissue samples; b) liver tissue samples; MTBE: methyl-tert-butylether, DCM: dichloromethane, ACN: acetonitrile, MeOH: methanol.

Talanta, Volume 286, 2025, 127442: Fig. 3. Boxplots visualizing the number of features extracted with the untargeted metabolomics workflow in positive ionization mode; n = 6 per extraction solvent (2 biological replicates and 3 replicate injections (technical replicates) of these); all relative standard deviations between replicates are <15 %; a) muscle tissue samples; b) liver tissue samples; MTBE: methyl-tert-butylether, DCM: dichloromethane, ACN: acetonitrile, MeOH: methanol.

4. Conclusions

Based on the tested and evaluated homogenization and extraction solvent parameters, it was found to be optimal to homogenize 20 mg of muscle or liver tissue with 200 μL (1:10 ratio) Water:MeOH (1:2), using 3 × 30 s pulses. After transfer of the supernatant, optimal extraction solvent was found to be MeOH:Acetone (9:1), resulting in the most comprehensive targeted and untargeted metabolomics, lipidomics and proteomics datasets. While it has to be stressed that a specialized sample preparation workflow, solely optimised for either of the three -omics techniques, might result in even greater data depth, the currently proposed workflow is suggested in cases where low sample amounts are available and/or multi-omics data integration is aimed for. Special emphasis of the current study was on fresh postmortem human tissue samples, with the view to analyse longitudinally collected human postmortem biopsy tissue samples to investigate the postmortem interval. While this method can serve as a basis for multi-omics studies in other matrices, the results would need to be confirmed. To counteract issues with the reproducibility of metabolomics/lipidomics technical injection replicates based on the pure organic nature of the extracts, it is recommended to use a separate vial for each technical replicate/injection (due to risk of evaporation through pierced lids). It was shown, that even for lipid-rich tissue such as liver tissue, monophasic extraction solvents seem to be suitable, not supporting previous propositions that biphasic extraction solvents are mandatory. In addition to the proposed sample preparation workflow, the current study has also shown that compound class identification seems to be a suitable evaluation criterion for metabolomics and lipidomics method comparison purposes, complementing classic evaluation parameters like “total number of features”. The use of MeOH:Acetone (9:1) as a monophasic extraction solvent system has the potential to be automated, allowing for high-throughput analysis of samples. Monophasic extraction solvents like MeOH:Acetone (9:1) are very frequently used as protein precipitation agent for example in routine clinical settings (e.g. detection of xenobiotics). This potentially opens the door for comprehensive multi-omics results from routine case samples in the future, massively extending possible clinical study cohorts.